Table of Contents

- Introduction

About

Indigenous Futurism Model-Making Competition

Building the Lenape Center

Natural Resources + Government Policy

Mapping + Urbanism + Community

Virtual + Augmented Reality

ISAPD Chapter Kit

National American Indian Memorial (1913)

By Anjelica Gallegos, M.Arch.1 2021

The contributions that Indigenous communities have made to our urban environments are made visible through ongoing digital mapping projects across the continent. Many of these maps render visible the community knowledge and collective histories of Indigenous experiences across time. Mapping projects and community cultural centers form the heart of Indigenous cultural continuity within the contemporary built environment.

In the early 20th century, Fort Wadsworth in Staten Island was set to become the site for the National American Indian Memorial. This article explores the history of that project.

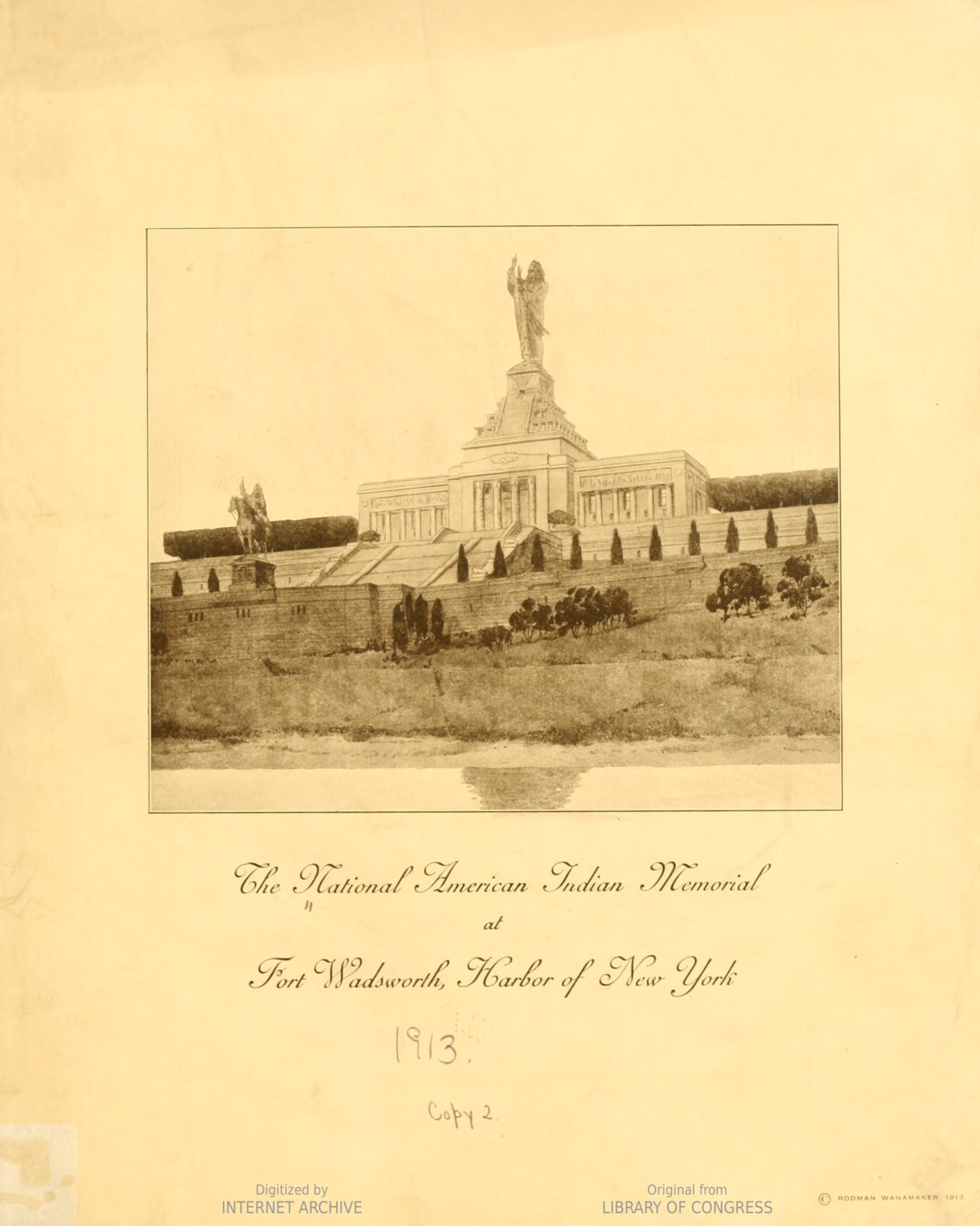

The National American Indian Memorial, a depiction of an American Indian man perpetuating the truth and dignity of First Americans, was meant to support the preservation of the character and lifeways of American Indians. The project’s program, which would include a museum, an art gallery, a library, and garden grounds, was to cover every aspect of American Indian lifeways, from regalia and artwork to architecture. At 580 feet tall, the memorial would have been taller than the Statue of Liberty, and would have been a feat of modern engineering, showcasing an innovative press, bolt, and anchor construction method utilizing cement. The statue was designed by Daniel Chester, known for the statue of Abraham Lincoln in Washington, DC’s Lincoln Memorial. It would have stood atop a Neo-Aztec pyramid, with an Egyptian Revival-style complex serving as its foundation, all designed by Thomas Hastings, a partner at Carrère and Hastings.

The idea for the National American Indian Memorial belonged to Philadelphia mogul Rodman Wanamaker. Between 1908 and 1913, Wanamaker sponsored a series of expeditions led by author and photographer Joseph K. Dixon to document various tribes throughout the United States. The expeditions were meant to generate public interest and support for American Indians’ right to citizenship, which they only gained in 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act. After receiving approval and support from the US House of Representatives, Wanamaker organized a “Committee of One Hundred” prominent Americans to support the project, including figures such as Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Cornelius Vanderbilt, J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, William Randolph Hearst, Henry Clay Frick, and Ralph Pulitzer.

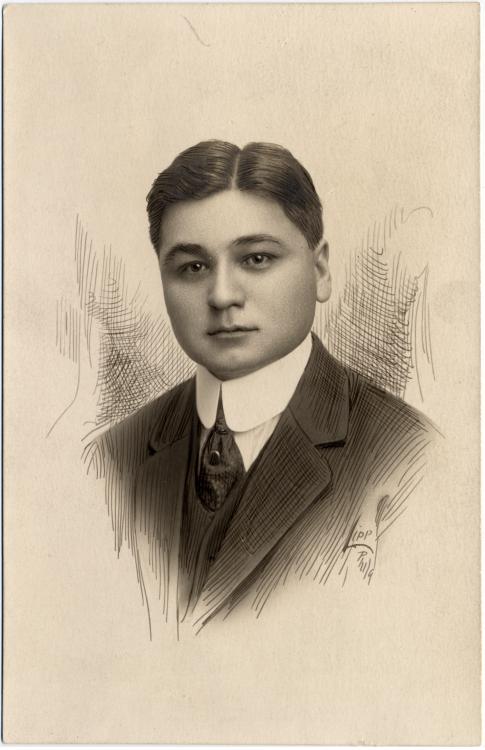

The American Indian Memorial project had a unique affiliation with Yale University. Thomas Hastings and his firm worked on projects for the university, including the Yale University Quadrangle, Woolsey Hall, and University Commons. Furthermore, Henry Roe Cloud, a member of the Winnebago Nation of Nebraska and the first American Indian to attend Yale, served as a liaison between tribal leaders and collaborators for the memorial project. Roe Cloud graduated from Yale with a B.A. in psychology and philosophy (1910) and a M.A. degree in anthropology (1912) and became an important figure who transformed American Indian higher education and government policies. He was also the only American Indian co-author of “The Problem of Indian Administration,” commonly referred to as “The Meriam Report,” an extensive survey made at the request of the Secretary of the Interior that evidenced the failures of federal Indian policy in the early twentieth century. This survey, presented to Congress in 1928, helped set in motion many of the subsequent reforms of the Indian New Deal of 1934.

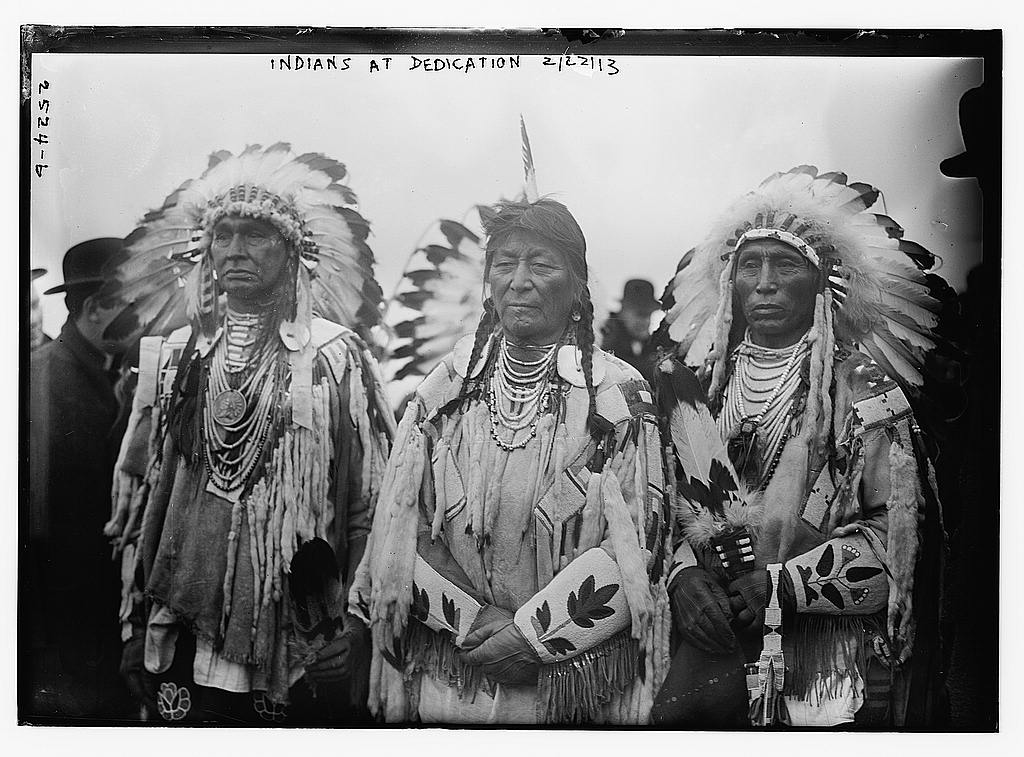

On February 22, 1913, President Taft broke ground on the project at Fort Wadsworth. The Committee of One Hundred was among the crowd, which also included governors, mayors, and naval and military officers. Thirty Indigenous leaders attended the groundbreaking ceremony representing the following tribes: Northern Cheyenne, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, A’aninin, Crow Creek Tribe, Crow Nation, Miniconjou Lakota, Oglala Lakota Nation, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Yankton Sioux Tribe, Blackfeet Nation, Southern Cheyenne Tribal Nation, San Carlos Apache Nation, Kiowa Tribe, Chippewa Tribe, the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag.

The ceremony included speeches from President William Howard Taft, Dr. Joseph Dixon, Chief Hollow Horn Bear, and Henry Roe Cloud, which covered the purpose of the Memorial, Wanamaker’s expeditions, the site’s history, and the state of affairs in Indian Country. The Buffalo or Indian Head Nickel was also released during this ceremony, part of President Taft’s efforts to beautify American coins and showcase American identity After the groundbreaking ceremony, Wanamaker organized several lectures sharing information about the expeditions he sponsored, but he was ultimately unable to raise sufficient funds for the project, which was further overshadowed by the United States engagement in World War I.

Though this project was never built, it remains an important part of American history, bringing together Indigenous leaders and academics, mainstream private society figures across fields, government officials, and military groups. The project used architecture as a political apparatus to generate public interest and influence government policy. However, while the museum was meant to preserve American Indian cultural artifacts and educate the public, the project nonetheless presented American Indians in a static, archaic, and romanticized lens that framed them as a dying culture. This erroneous conceptualization of American Indians as a “vanishing race” that would soon cease to exist was perpetuated throughout the 20th century and has contributed to the erasure of Indigenous histories while hindering pathways to acknowledgement and resolution. Furthermore, it has deeply impacted the public’s perception of first Americans, influencing how American history has been taught for generations.

Knowing American Indian history is knowing American history. Sharing and seeking knowledge contributes to an informed consciousness that challenges the amnesia of identity and an amnesia of place. While unrealized, the National American Indian Memorial serves as an example of why it is important for architecture and the programs it houses to elevate people through increasing connection with place, acknowledging the history of the site, and contributing toward a living identity of the communities architecture is interwoven with.

Further Reading

“Native presence at Yale is celebrated during Henry Roe Cloud conference,” YaleNews, November 7, 2017.

“Henry Roe Cloud Dissertation Fellowship Announced for 2021/22,” Yale Group for the Study of Native America.

“Ceremonies Attending the Official Inauguration of the National American Indian Memorial at Fort Wadsworth,” February 22, 1913, Courtesy of the Library of Congress.