Table of Contents

- Introduction

About

Indigenous Futurism Model-Making Competition

Building the Lenape Center

Natural Resources + Government Policy

Mapping + Urbanism + Community

Virtual + Augmented Reality

ISAPD Chapter Kit

A New Vision of Fort Wadsworth (2020)

In the fall of 2020, Anjelica S. Gallegos participated in the advanced design studio, “Productive Uncertainty: Indeterminacy, Impermanence, and the Architectural Imagination” at Yale University. Taught by Marc Tsurumaki and Violette de la Selle, the studio engaged the fundamental paradox of uncertain impermanence in a practice predicated on permanence. It questioned how the material conditions of architecture might engage with the increasing volatility that characterizes our collective relationship to emergent environmental, climatological, biological, political, and social conditions. Topics explored included the membrane as a mediator of perception, the influence of the gaze, and the fortification of natural elements, including water. This article outlines her designs for the Four Waters Formative, a Living Laboratory for Indigenous Ecological Knowledge.

Read about the early 20th-century history of Fort Wadsworth here >

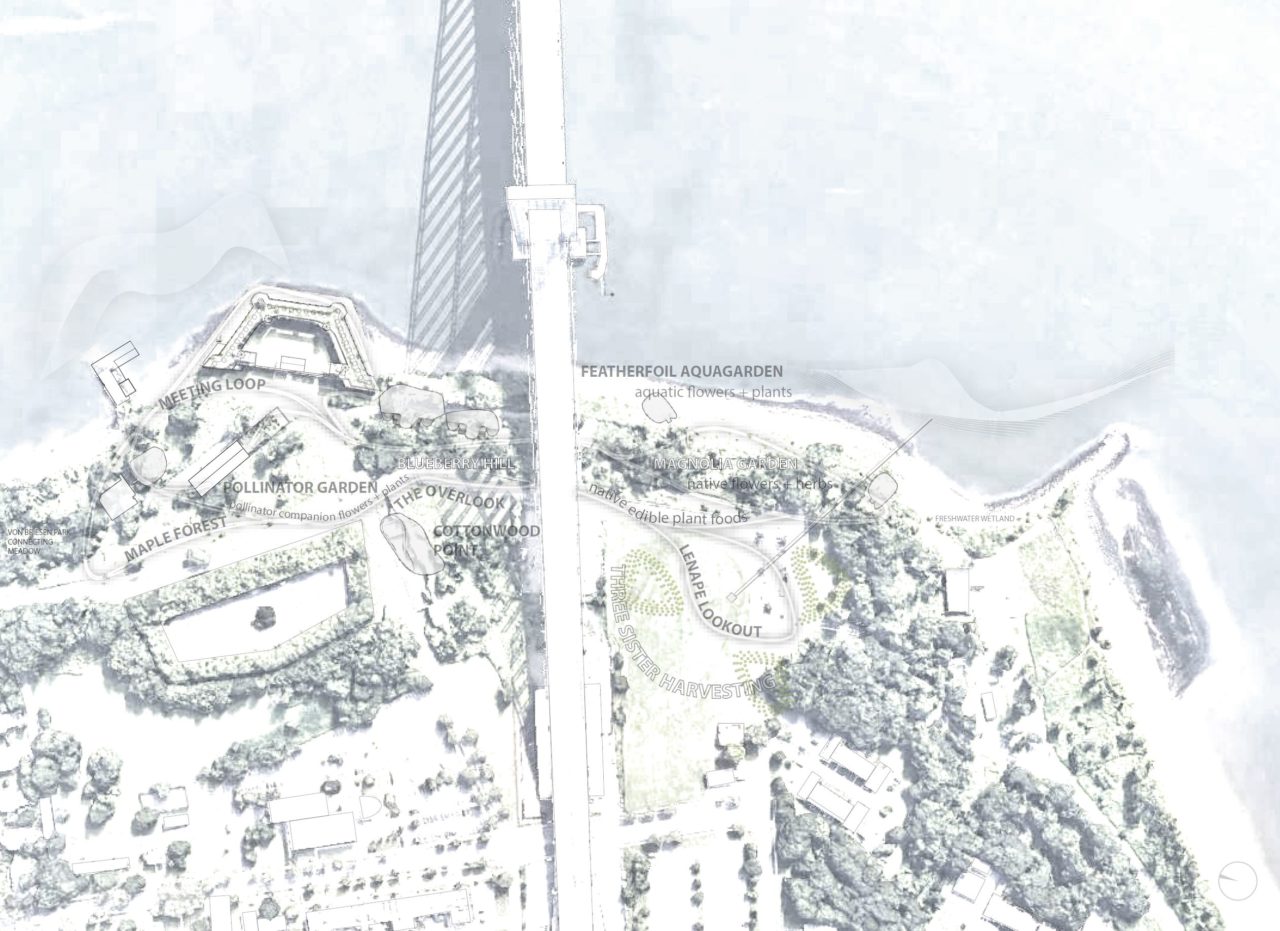

Located on the site of Fort Wadsworth in Staten Island, NY, Four Waters Formative is a Living Laboratory for Indigenous ecological knowledge, integrating adaptive design, land remediation, and historical preservation. Fort Wadsworth (here renamed Four Waters Formative), is a federally owned site that is considered part of the Gateway National Recreation Area. Four Waters Formative reinterprets the National Park and the historically preserved military site, serving as a place to promote the collaboration between the greater public, tribes, and federal programs through the introduction of on-site education.

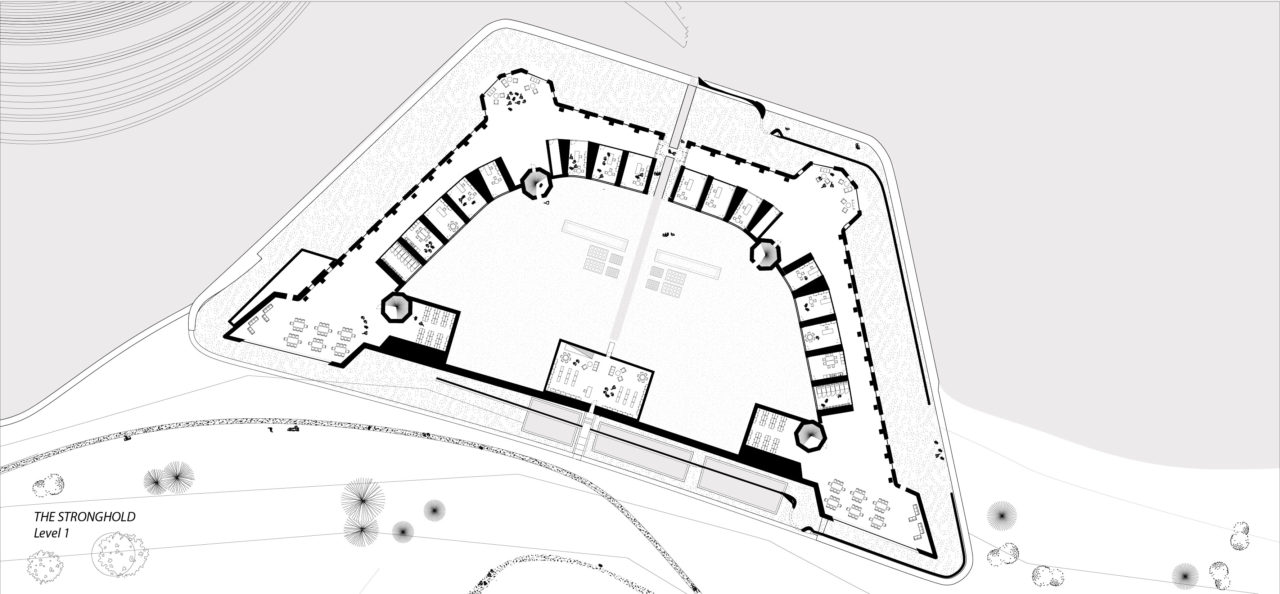

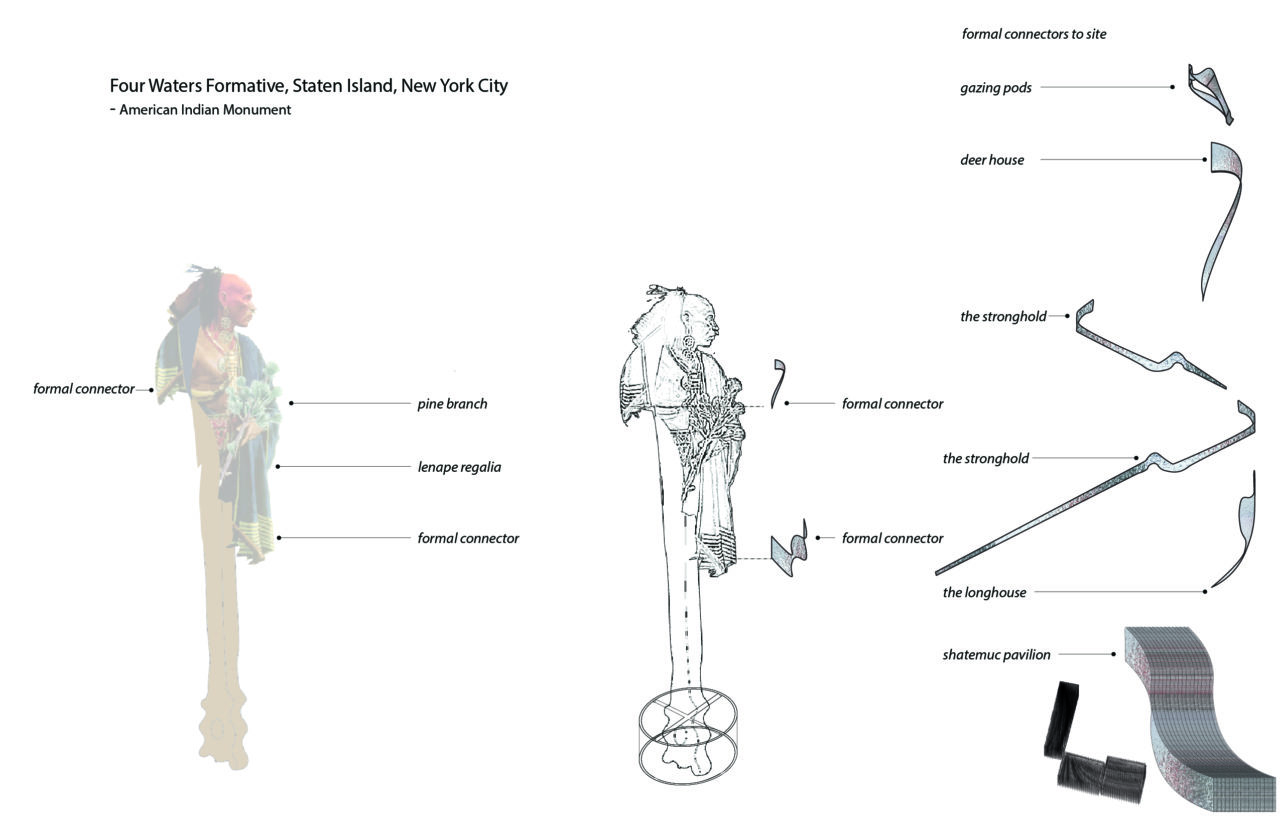

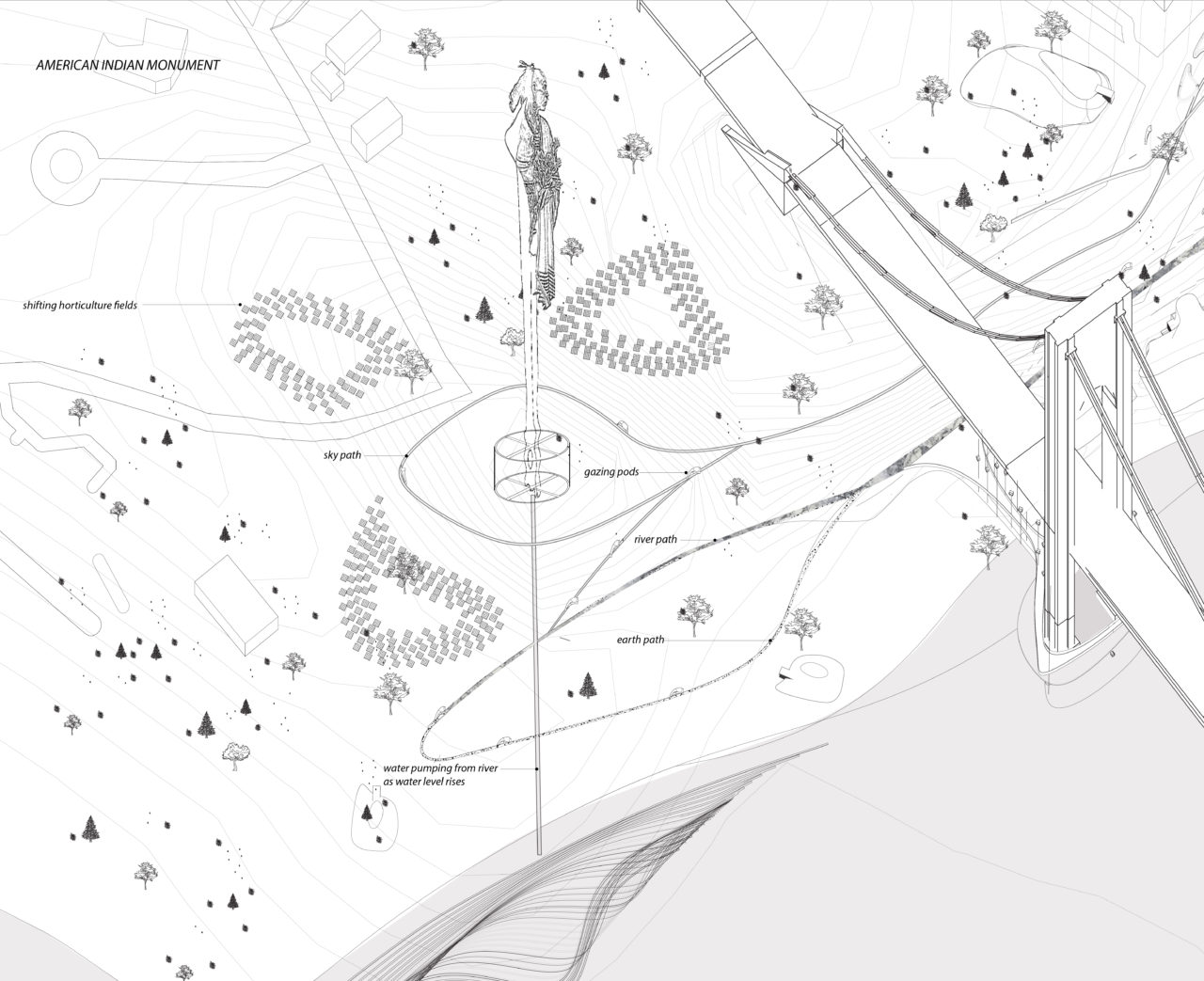

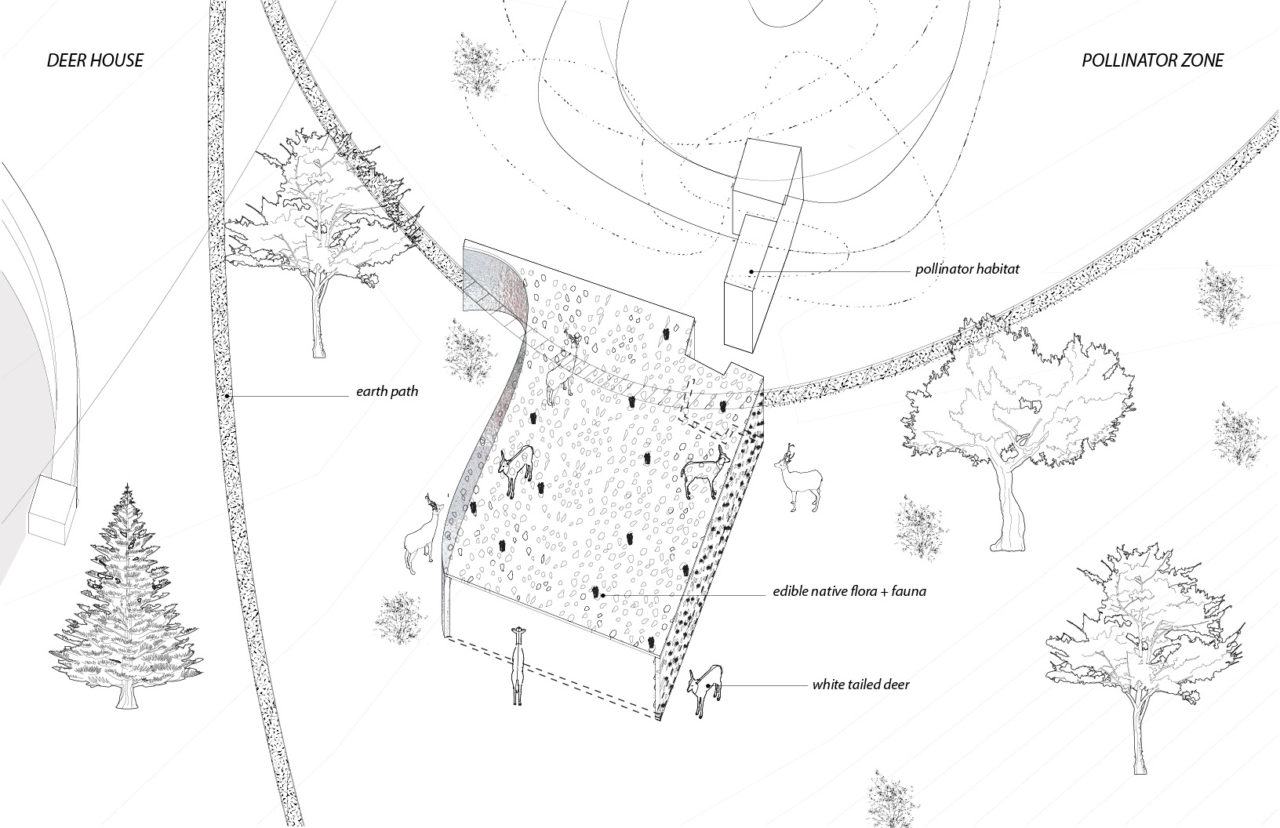

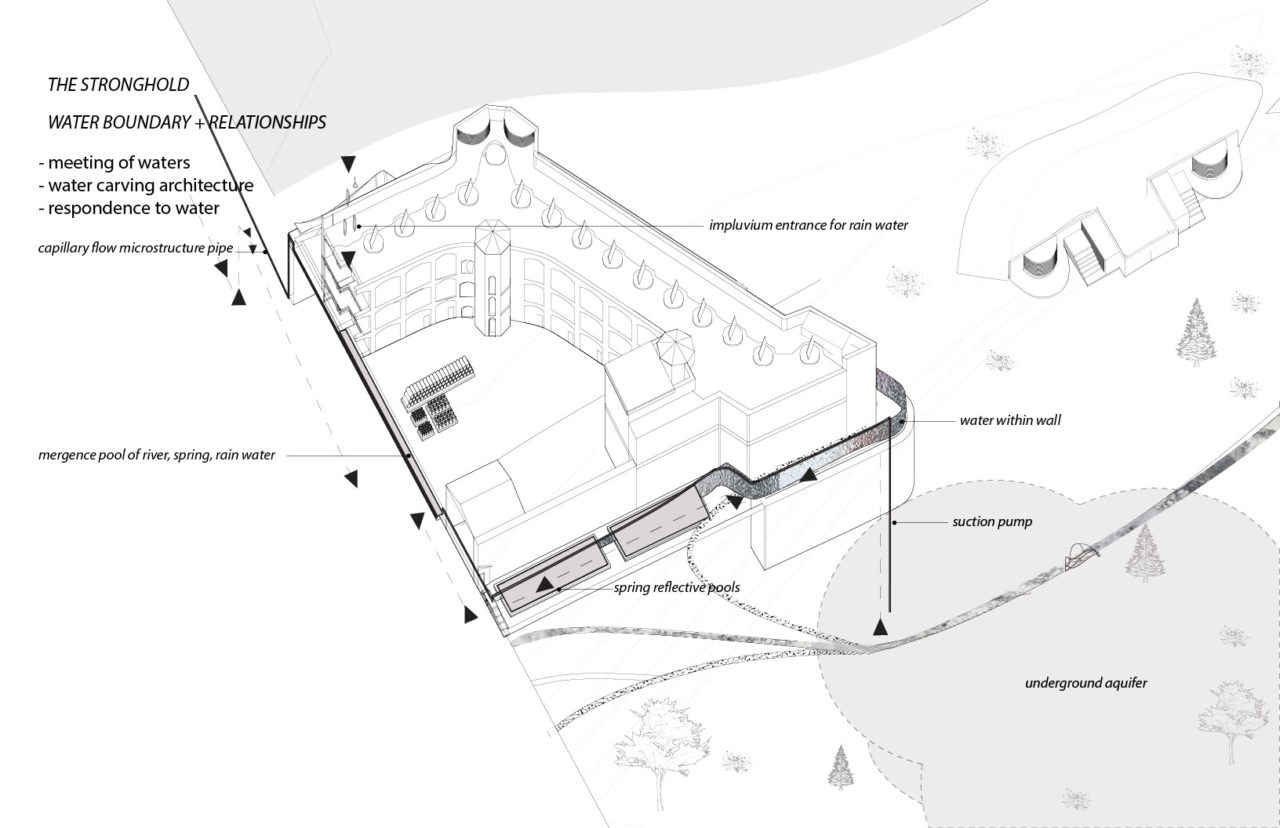

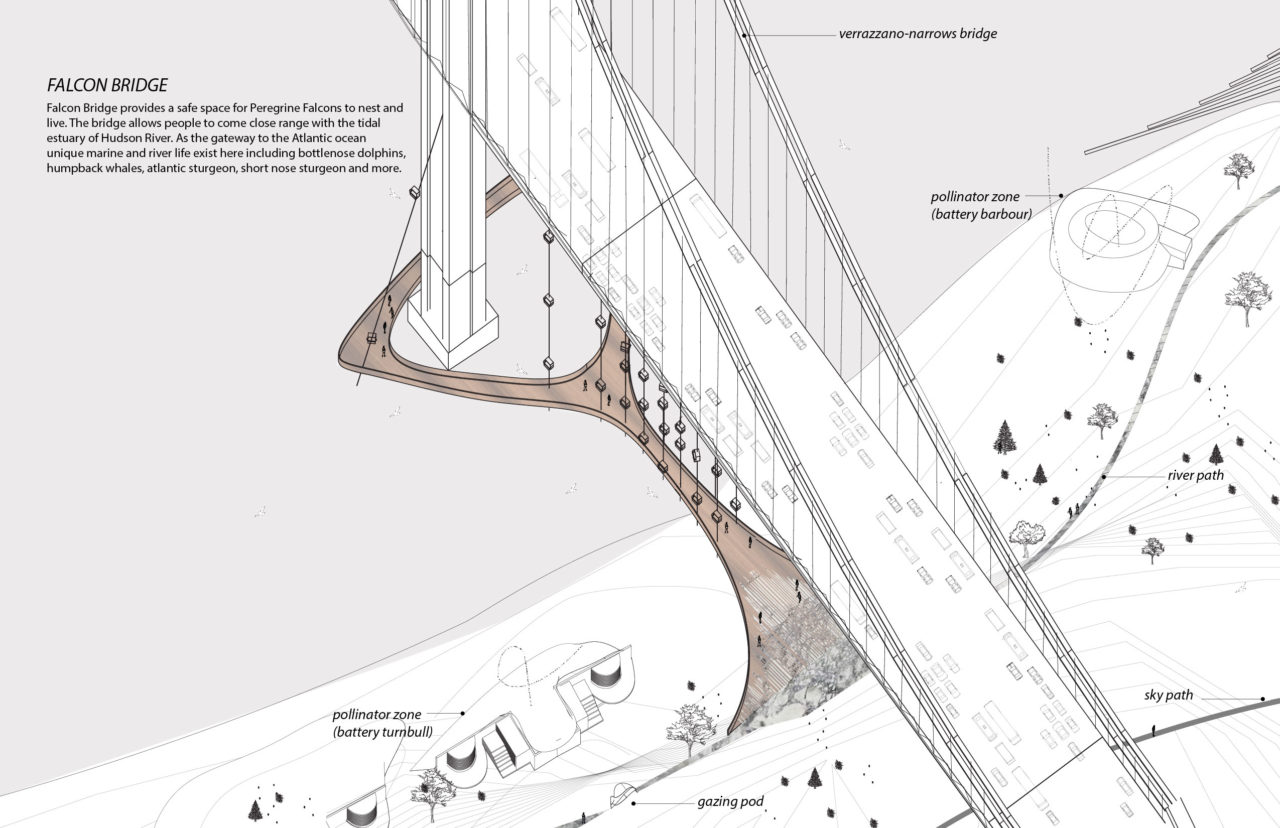

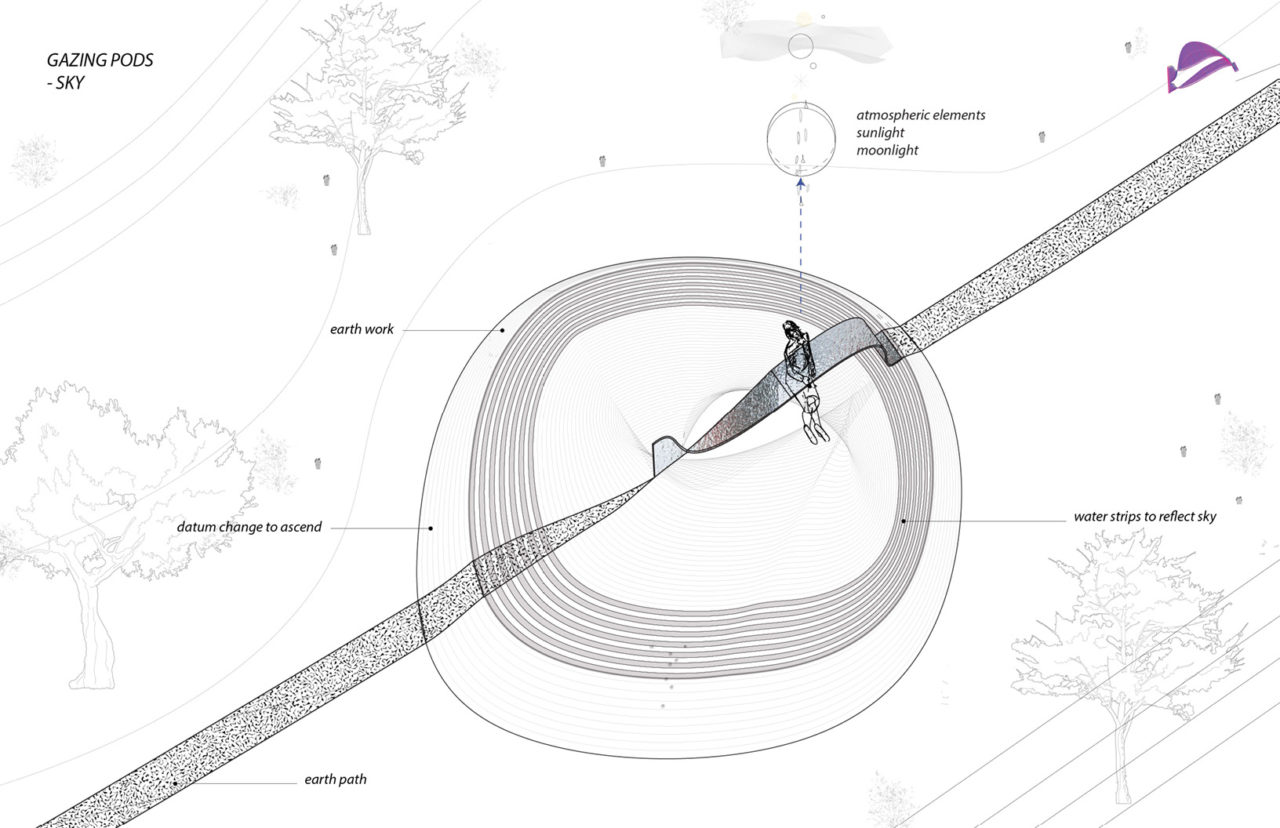

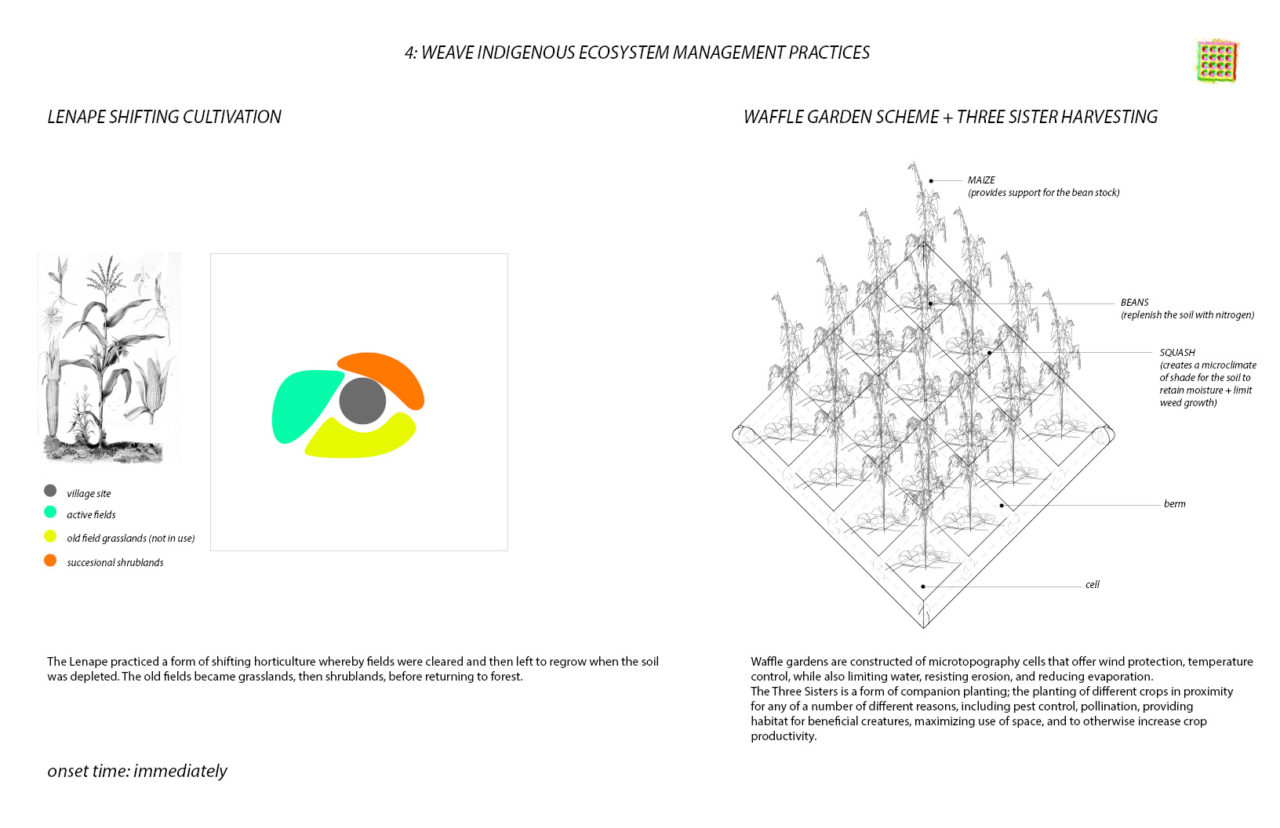

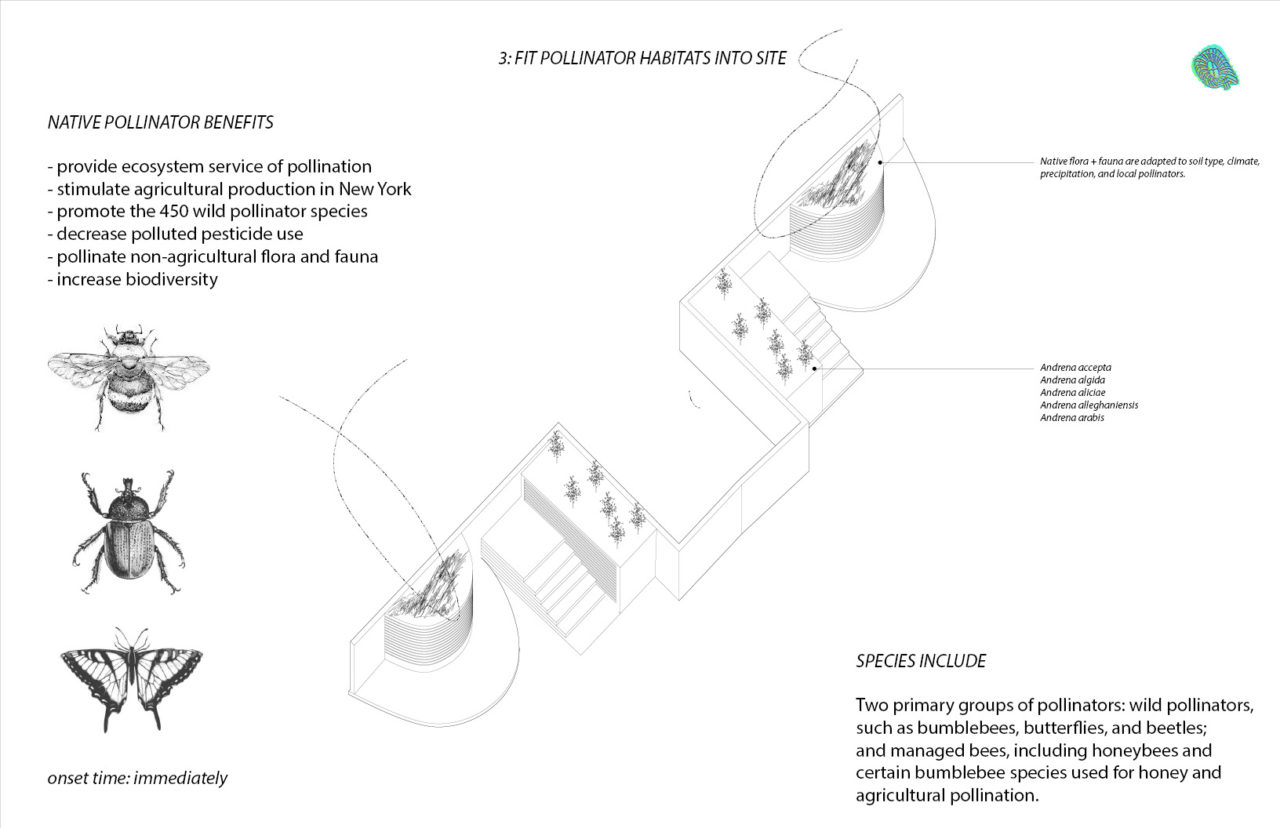

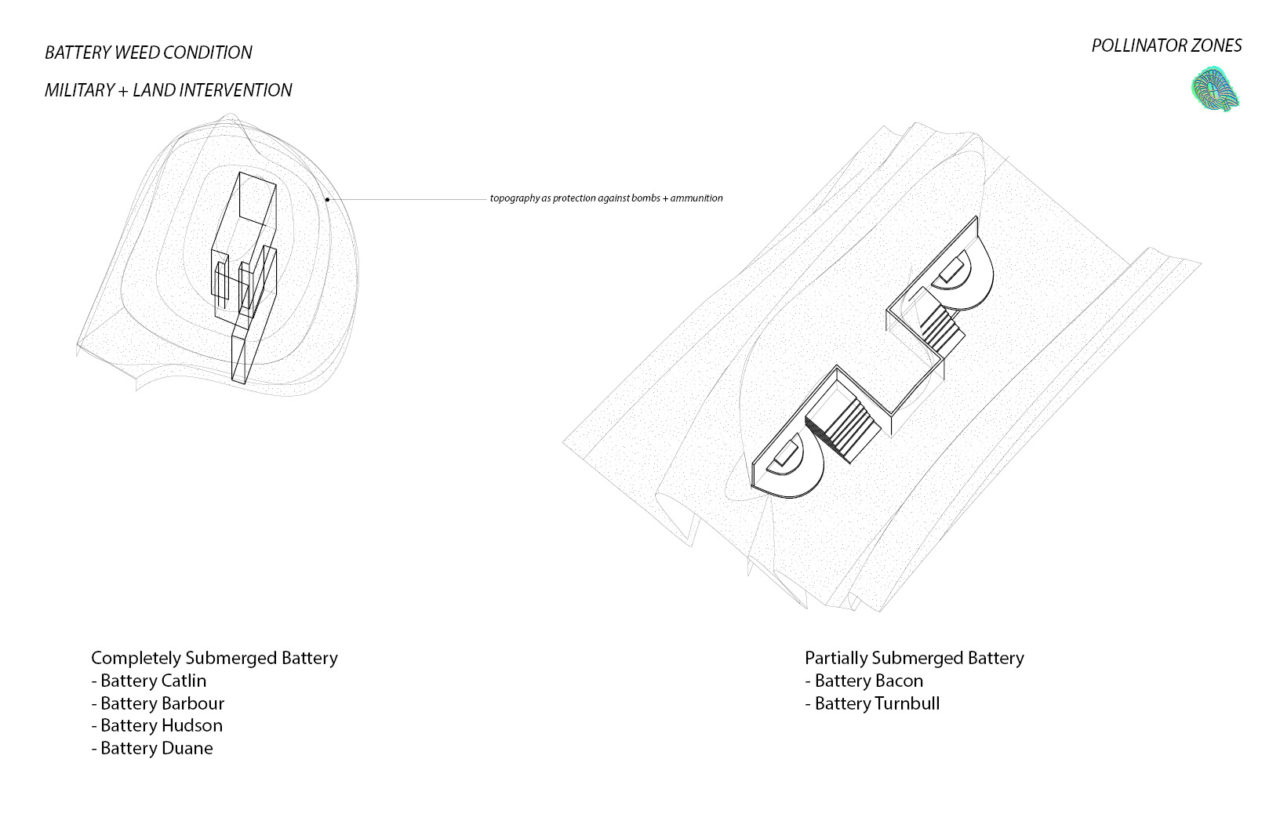

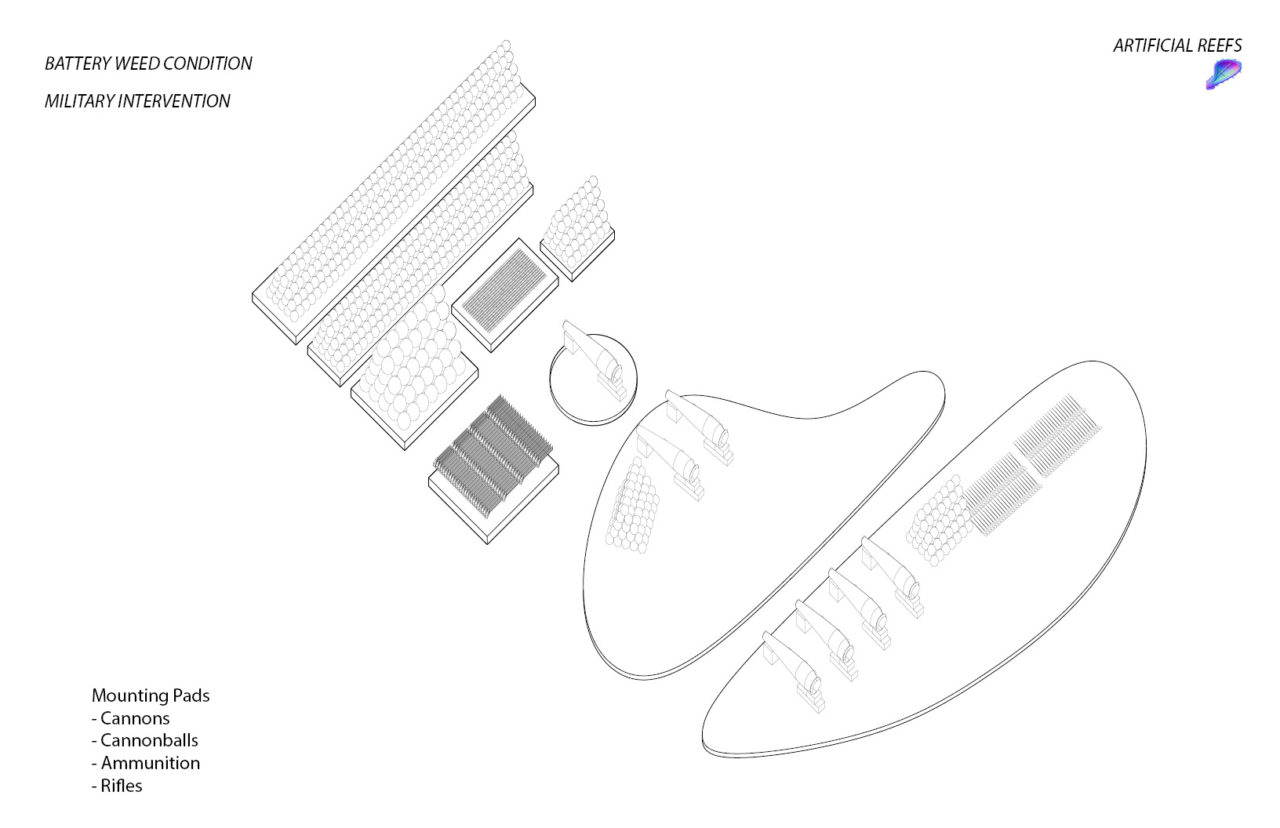

Focusing on incremental adaptation, the range of site interventions have varied onset times and serve different connected members of the community, including animals. The projects system of paths weaves together these interventions, which include gazing pods, artificial reefs, pollinator batteries, and earthworks, creating a series of varied garden spaces. The Formative’s built interventions preserve, reference, and rebuild historical structures with historical and proposed materials while also introducing new original designs.

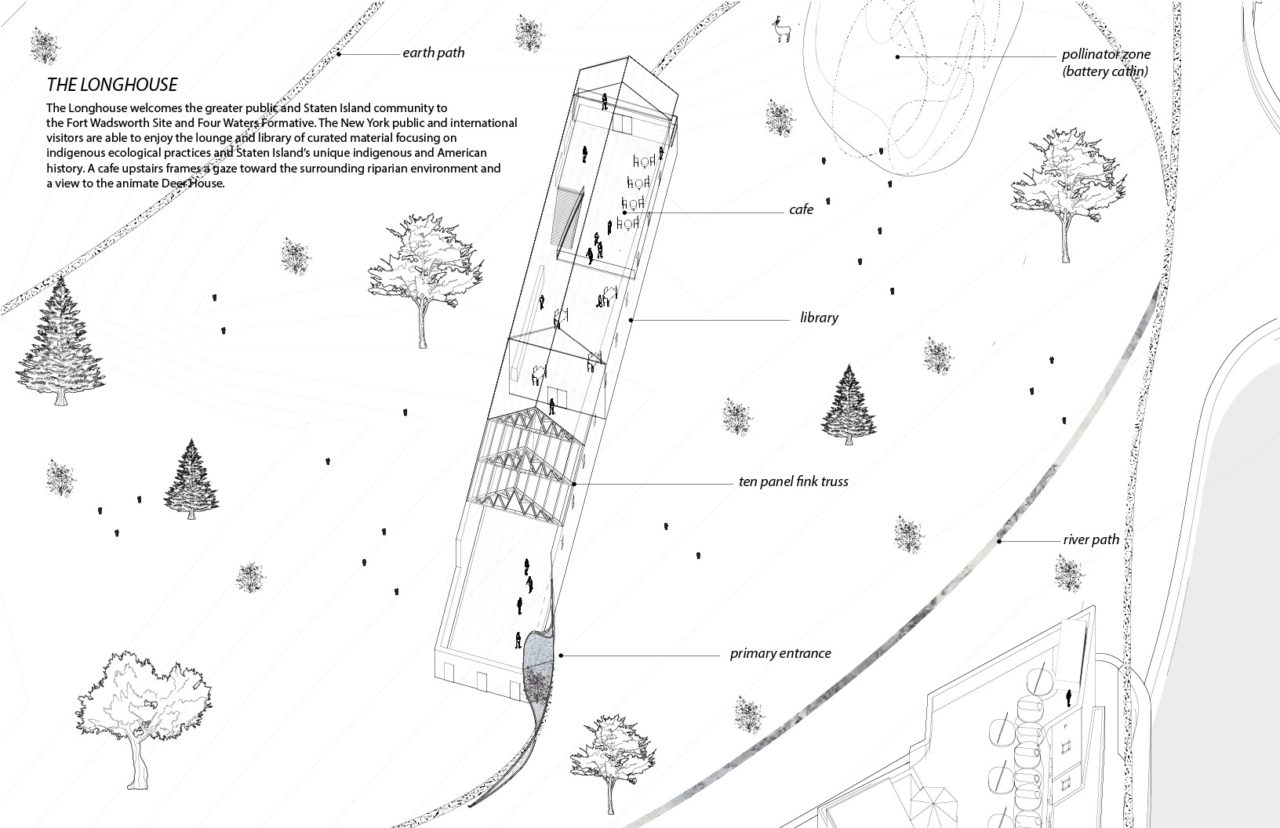

The program centers around the Stronghold, which serves as a gathering place with redesigned spaces that act as small and large offices and presentation rooms. Shatemuc Pavilion, named after the Lenape name for the Hudson River, is built on a renovated dock, where the sounds of the river and wind patterns can be experienced by way of PV tubes. The Deer House is a partially submerged former battery that incorporates growing greenery within its rebuilt walls. The Longhouse, a lounge and library, welcomes the Staten Island community and the greater public to enjoy curated material focusing on Indigenous ecological practices and Staten Island’s unique Indigenous and American history. A cafe upstairs frames a view of the surrounding riparian environment and the Deer House. Falcon Bridge, which runs parallel to the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge, promotes the livelihood of the site’s peregrine falcons by way of built structures for nesting, while also serving as a gauge to monitor change in water level.

In the early 20th century, Fort Wadsworth in Staten Island was set to become the site for the National American Indian Memorial. Depicting an American Indian man perpetuating the truth and dignity of First Americans, the memorial was meant to promote the preservation of the character and lifeways of American Indians through a program that included a museum, an art gallery, a library, and garden grounds. In response to this historic proposal, Gallegos designed a monument that celebrates Indigenous resiliency. The stance, reference to the local Lenape tribe, and its dynamism of the monument are meant to respectfully transform the meaning of the monument. To emphasize the uniqueness of Indigenous ecological relationships, the monument serves as a physical gauge, data collector, and visual indicator of live environmental information. As the water level rises in the adjacent Hudson River, the height of the monument changes as well. The monument also tracks contaminants in the river and air pollutants over the Staten Island area, dispersing the live data through the network of gazing pods along the path system. The project leverages technology as a tool to rekindle and remediate ecological knowledge and visualize interconnection.