by Center for Architecture

The Center for Architecture’s latest exhibition, New Practices New York, showcases the six winners of the most recent cycle of AIA New York’s New Practices New York competition, which serves as a platform for recognizing and promoting young and innovative designs firms in the city. This series will introduce you to the winning firms, offering a glimpse of New York City’s bright architectural future. Next up: BRANDT : HAFERD.

Want to learn more about the firm’s growing portfolio? Join us for a live conversation with BRANDT : HAFERD on Thursday, January 12, 6:30-8pm at the Center for Architecture.

Partners:

K Brandt Knapp & Jerome W Haferd

Most Recently Constructed Project:

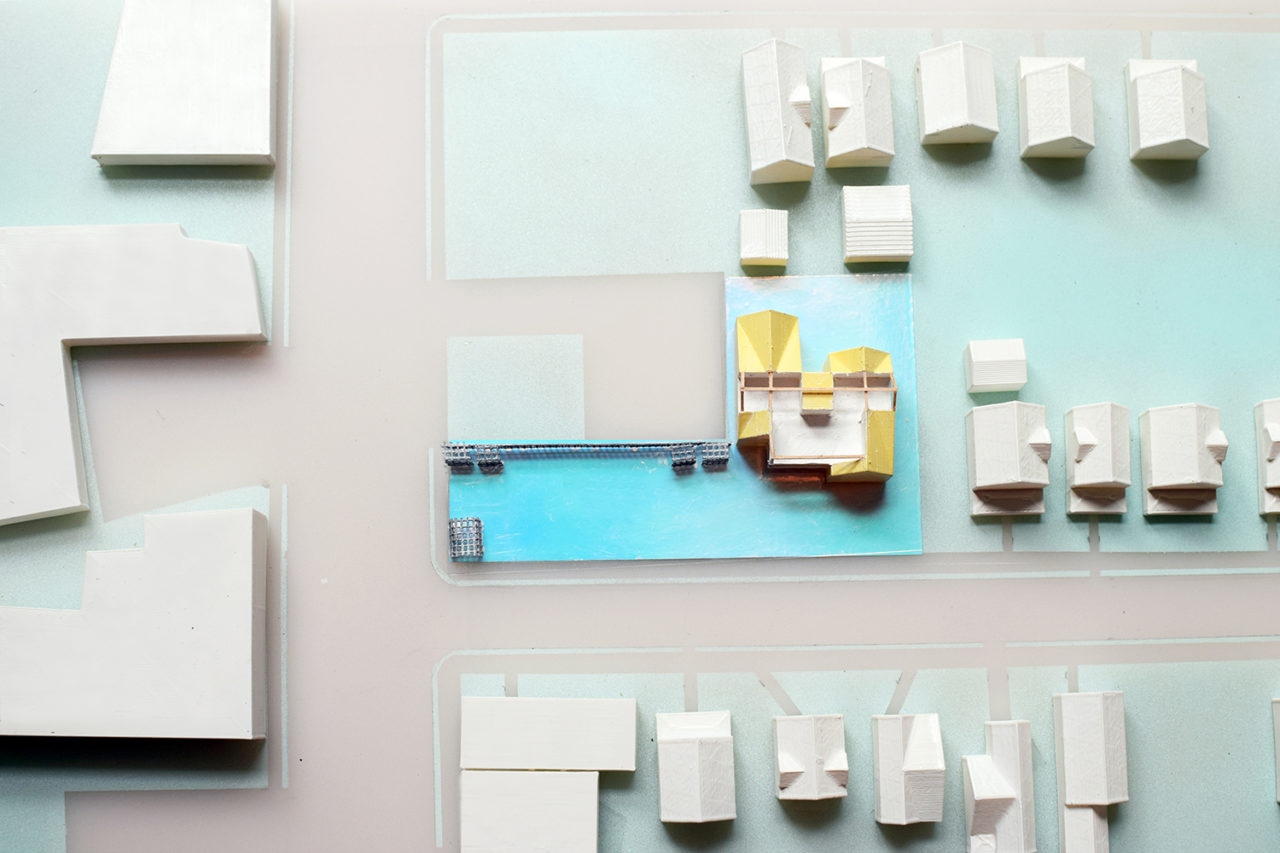

National Black Theatre Home Office and Archives, 2022

Three words to describe your firm’s design philosophy:

Community-driven, intersectional, regional

How would you define your work and in what context?

As BRANDT : HAFERD, our identities have led us into a diversity of communities and spaces. Performance and play, abstract vs. built form, nature and territory, and the individual vs. the collective were some of our founding provocations. Ten years on, our practice still seeks to 1) form new collaborations with artists and other disciplines; 2) transect a unique, underserved “geography” of practice; and 3) shape the emerging public realm.

What drove you to start your practice?

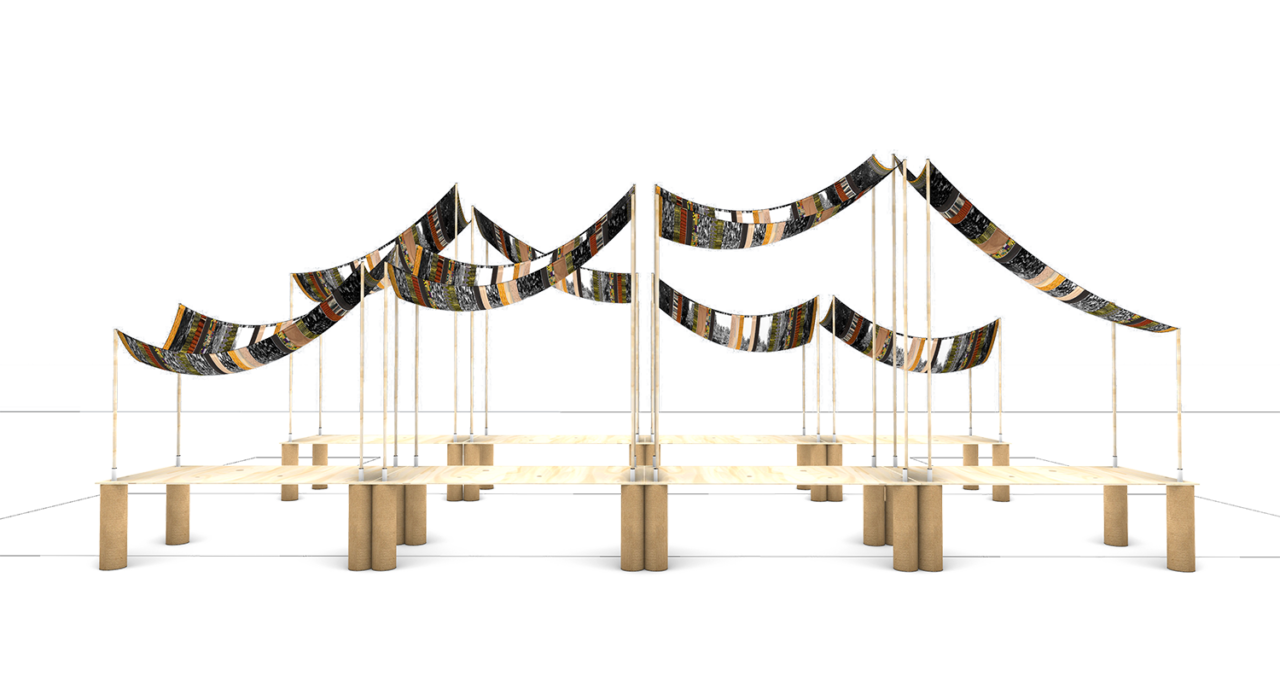

We had a strong desire to create public installations and have more freedom in how we shaped our creative practice. Then, we won a competition in 2012 to build the Folly pavilion at Socrates Park, which kickstarted the practice.

What is your approach to design?

In short, what motivates us is a desire to build, but, most importantly, to build in contexts that fall outside mainstream attention and the economy of the high-end design world. This hasn’t been easy and has pushed us to expand our definition of architecture. Inspired by sites and cultural practices, we’re starting to embrace the multivalent capacity of our works. We’re embracing how the ephemeral and the built operate as a choreography and as part of a larger civic infrastructure that blurs the line between inside and outside, private and public, “happening” and structure. Liminality, enclosure, and territory have remained transcendent concepts that drive our architectural project.

How do you create an atmosphere that’s conducive to creativity in your practice and work?

We often connect our own interests and academic research to new project opportunities and explorations. Thus, at any given time, many of our projects are related to our preoccupations and geographic interests. Teaching and community engagement remain a key element to our studio and how we work, which keeps things engaged and fun.

What influences are most meaningful to your firm?

Our different intersectional identities have always bonded us and shaped our practice. We began our collaboration in 2008 as graduate students at Yale. Female, Black/mixed-race, both LGBTQ+, from rust-belt cities and state schools—there was a solidarity as “misfits” at Yale and in architecture.

Our community here in Harlem has also been a huge influence, including the area’s Black and indigenous history and the contemporary cultural landscape. Years of working day jobs, then long nights hammering, renting U-Hauls, writing grants, and attending community meetings formed us. Our local network in Harlem gradually became clients—and a community-driven practice developed out of necessity and intention.

What is your favorite building in New York, and why?

Jerome: My favorite building in New York is probably the Fire Watchtower and Acropolis of Marcus Garvey Park where it sits. Not exactly a building, but a partially constructed landscape that harbors and facilitates a number of publics and creates numerous spaces for civic expression and enjoyment in Harlem. I’ve also always loved Lerner Hall by Bernard Tschumi, a mentor of mine.

How is your approach to design influenced by New York City? What are you doing in New York?

Our practice has grown out of producing community-driven projects with local stakeholders in and around New York City, in particular Harlem. The public nature of many of these projects, as well as the collaborative dimension of producing the work with local artists and in the urban fabric, has greatly influenced how we practice. Our work in Harlem and New York continues, with a the upcoming completion of a project for the National Black Theatre and a series of wellness pavilions developed with Harlem Grown and other local non-profits.

How do you see your work resonate in the wider culture?

Our aim is to unlock under-represented voices and histories and to produce unique public spaces and activity. We’ve dedicated ourselves to designing for and with historically marginalized stakeholders and to engage sites of structural disinvestment and of African American and Indigenous history in New York, Newburgh, Cleveland, and elsewhere. Our dream is for this to grow and expand and demonstrate that small, embedded practices can be part of cultural and civic transformation.

How did your firm change in the last two years of collective pause? What insights and ideas emerged?

The last two years have been a transition time for us and our practice, as we establish a base in the Hudson Valley, parent newborn children, and expand advocacy and spatial work to a national level.

What new opportunities did the collective pause present that changed how you practice? How do you see the field changing in the future?

The disruption of COVID, hybrid work, and physical splitting of our base between NYC and the Hudson Valley prompted us to expand our constituency and areas of focus. BRANDT : HAFERD is expanding in both regional scope and project scale— with much of our current effort focused on positioning our practice to be part of larger teams and/or civic projects. While we believe it will pay off, a lot of this effort at the moment is our own investment.

What new forms of architecture are you doing?

On a local level, we’re continuing to experiment and build public space projects that integrate local culture, aesthetics, performance, and new ideas of belonging into the architecture itself. Additionally, our work in New York is changing to reflect the evolving urban streetscape of the city. Regionally and further afield, we are now beginning to explore larger scale projects that operate at the scale of the neighborhood, block, or even territory. We’re working on housing and a forest watchtower, projects that create community and place in less dense or traditionally urban environments.

Learn more about the winners of the competition at our New Practices New York exhibition, on view through February 4, 2023.