by Bill Millard

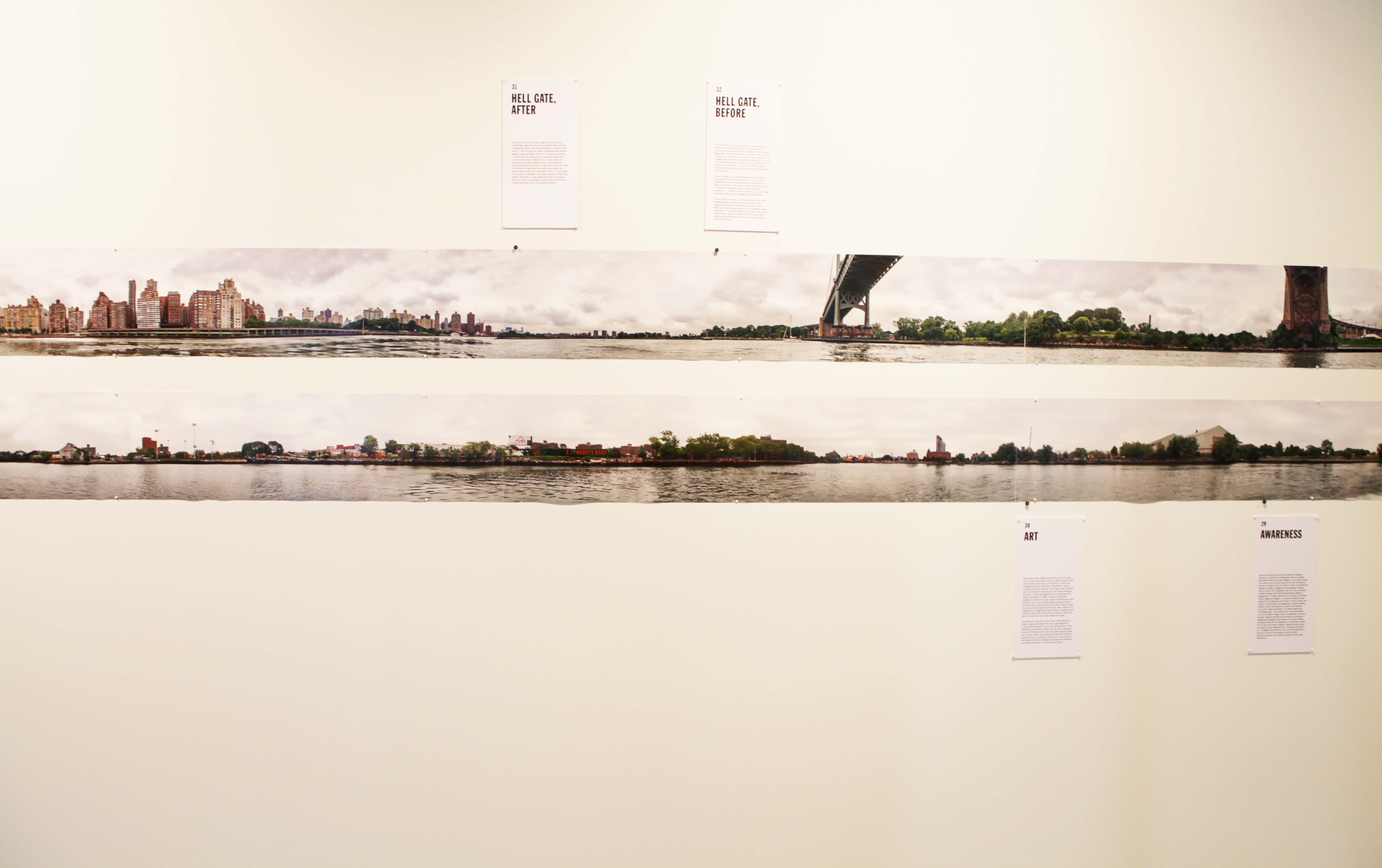

At the intersection of history, art, and literature, Elizabeth Felicella and Robert Sullivan’s “Sea Level: Five Boroughs from Water’s Edge” presents the complexity of the East River waterfront through an ostensibly simple form: two enormous panoramic composite photographs mounted in parallel and accompanied by interpretive prose. Capturing time through this linear assembly of water-level images, the exhibition shows how New York has developed over the decades while retaining components of its maritime and industrial past. It is a must-see show for anyone interested in the city’s evolution and the myriad stories its built environment contains.

With the launch of the pop-up space Center at the Seaport and the opening of “Sea Level,” the Center for Architecture has also become a publisher: the exhibition’s catalogue is a 112-page paperback of Sullivan’s texts, which accompany Felicella’s images in the exhibition. Cynthia Kracauer, AIA, the Center’s managing director, opened the discussion of “the water as a character in the drama of climate change” – a centuries-long and open-ended narrative, she noted, observing that “New York was a seaport before it was much of a city” – by invoking a famously paradoxical excerpt from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Felicella performed such an exploration last this past July, cruising on the yacht Kingston from Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island, underneath the Verrazano Bridge, then out to Fort Totten in Queens, taking more than 1,300 frames on each side of the water with a timer-triggered DSLR camera. A former Design Trust for Public Space photography fellow who has also documented the city’s branch libraries, she enthusiastically told the opening audience how, after being paired with Sullivan for the project by Kracauer, she initially set out to take only 10 to 20 photos, but simply “couldn’t stop shooting” and ended up covering the whole waterfront in two passes. Her work, conjoined with Sullivan’s, presents the city’s bridges and islands, its ruins and Superfund sites, its gleaming and gentrifying redevelopments, the occasional landmarked warehouse (Cass Gilbert’s Egyptian-themed Austin, Nichols & Company building next to Domino Sugar), and isolated green promontory (“Astoria Mountain” near Hunters Point, possibly created from Lincoln Tunnel excavation material, but of uncertain origin, “a last sad hill, as triumphant as it is anxious”). Photo editor/retoucher Jeremy Gillam selected about a third of the full collection and created the elongated Photoshop composites. (Sullivan has also posted a whirlwind condensation of the shoot as a two-second YouTube video.)

Forts Wadsworth and Totten, as starting and ending points, anchor the project in the region’s military history, one of several areas of recurrent emphasis in Sullivan’s texts. Sullivan, a contributor to The New Yorker, Vogue, and other publications, and author of the well-received 2004 book Rats (yes, he lurked in an alley off Fulton Street for a year researching that one), is a close, incisive observer of evolving activities along the city’s waterfront – commerce, residence, transportation, defense – and of the prolonged social conflicts over which groups’ interests these spaces would serve. In detailed segments dedicated variously to sites, commodities, or concepts, he sketches waterfront locations’ roles in national struggles against colonialism, seceding slaveholders, or the Axis powers (Wallabout Bay, for example, hosted British prison ships during the American Revolution; the first modern battleship, the Monitor, was built for the Civil War at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which also housed workers returning from the Navy during World War II). He also imaginatively connects military episodes with today’s struggles, noting in a passage on the evacuation of Brooklyn by boatmen from Marblehead, MA, that the city’s sandy beaches, once far more numerous around the harbor, “in 1776 turned out to be defensive attributes, as they are in a warming world fighting rising tides: penetrable by water and by people, and replenished, rather than destroyed, by the tidal strait…. Think of how the Marbleheaders worked with the tides rather than fighting against them.”

Felicella’s images appear deceptively straightforward while generating tricks of perspective; close examination shows angles continually shifting with the Kingston‘s movement along the shores, generating a nowhere-yet-everywhere perspective that alters one’s sense of observational time. Likewise, Sullivan’s prose juxtaposes major icons like the UN building and forlorn, uninhabited features like North and South Brother Island (off-limits to anyone but biologists) without letting their relative familiarity dictate the proportions of attention devoted to them. Fragments of cultural shrapnel associated with certain sites appear without overt explanation, but with the random charm of surrealist poetry: one learns to associate Beechhurst, Queens, with stars in the rising motion-pictures industry of the 1920s, naval minesweepers in the 1940s, and the 1930s radio voice of Popeye, Beechhurst resident Floyd Buckley, who originally sang of his show’s sponsor, not spinach: “Wheatena’s me diet / I ax ya to try it / I’m Popeye the sailor man!” The organizing method here is pure free association, and Sullivan aptly compared the opening discussion to the loopy conversation of 1970s teenagers listening to psychedelic rock in an altered state, ultimately winding up the proceedings with another Center first: a singalong performance of “Shenandoah” on accordion, inclusive and wistful like a day drifting among memorable sites and site-specific emotions.

Bill Millard is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in Oculus, Icon, The Architect’s Newspaper, and other publications.

Event: “Sea Level: Five Boroughs at Water’s Edge” Exhibition Opening and Conversation

Location: Center at the Seaport, 181 Front Street, 09.10.2015

Speakers: Robert Sullivan, Author and Curator; Elizabeth Felicella, Photographer; Cynthia Kracauer, AIA, Managing Director, Center for Architecture (introduction)

Organizers: Center for Architecture

Sponsors: Seaport Culture District/Howard Hughes; Classic Harbor Lines