by Tim Hayduk

On a Saturday in mid-September, a group of architecture and history enthusiasts joined the Lead Design Educator of the Center for Architecture Foundation on a walk through portions of the South Street Seaport Historic District. The ramble introduced the group to ways of “reading the streetscape” through conversation and a guided look at the mercantile structures in this once vital waterfront. The district preserves early building practices including the handsome Schermerhorn Row, a warehouse that was essentially the World Trade Center of 1811. Constructed of robust load-bearing brick walls, closely spaced wooden floor joists, and relatively small windows, the structure was not terribly sophisticated considering what the rest of that century would bring regarding architectural technology. Built on trash and soil excavated from hills further upland, Peter Schermerhorn hastily built the Row on landfill as a speculative development. The crooked lintels over the windows are the result of his haste – he did not allow the landfill to settle properly. The elements of a storyline began to appear in the details that the group was discovering and reading together.

Nearly 50 years ago, those who fought to preserve the South Street Seaport envisioned saving the neighborhood to reflect the fortitude of the working waterfront. The collection of buildings remains a place of trade – though the commodities have changed with the produce, fish, and dry goods that occupied the counting houses, stalls, and market buildings having moved elsewhere. The festival marketplace of the 1980s continues to reinvent itself. The architects at CookFox have turned a once decrepit block of Front Street into a wonderful mixture of stabilized buildings and new infill structures, adding up to a viable, attractive neighborhood one block north of the Fulton Street retail corridor. Old painted signs advertising salmon, halibut, and a company named Knickerbocker informed us of what had once been. We became archaeologists of building façades in search of human activity and intentions.

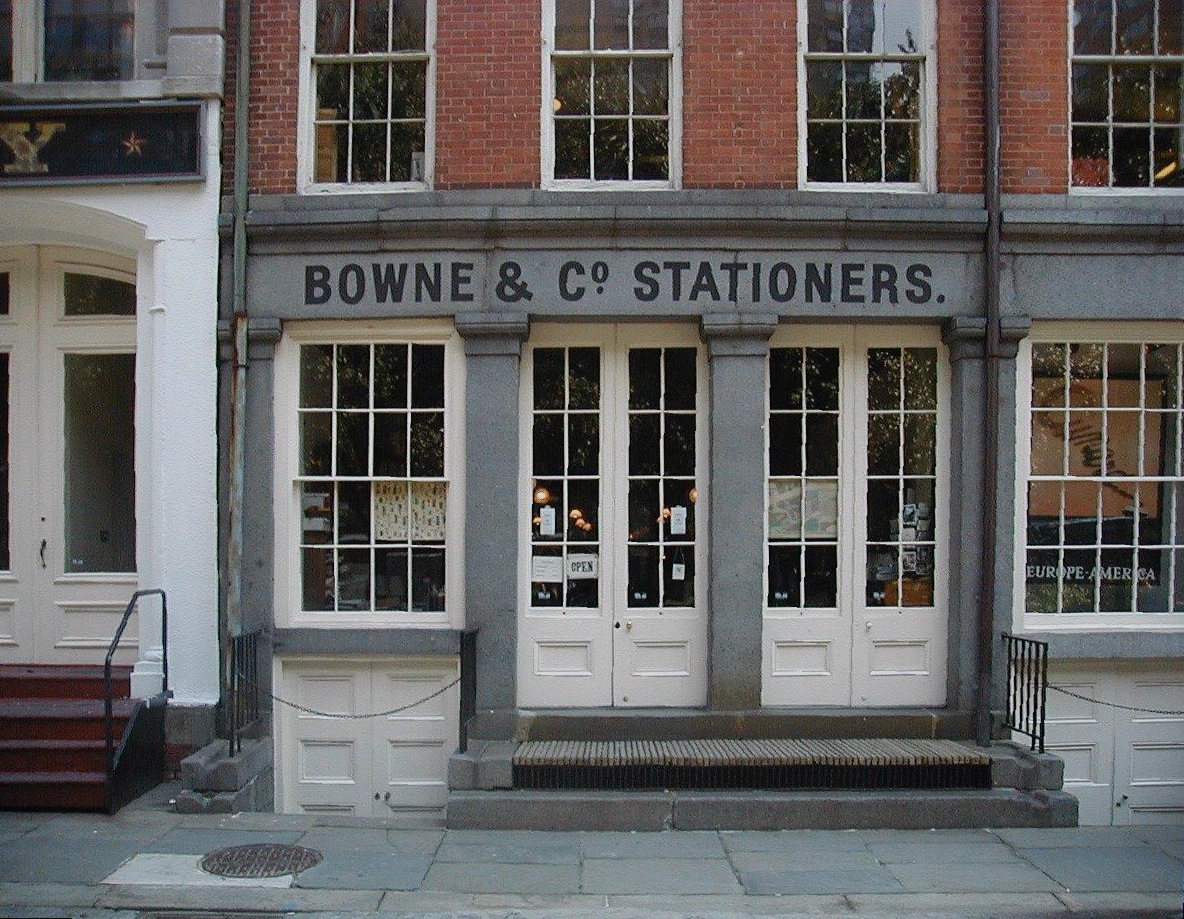

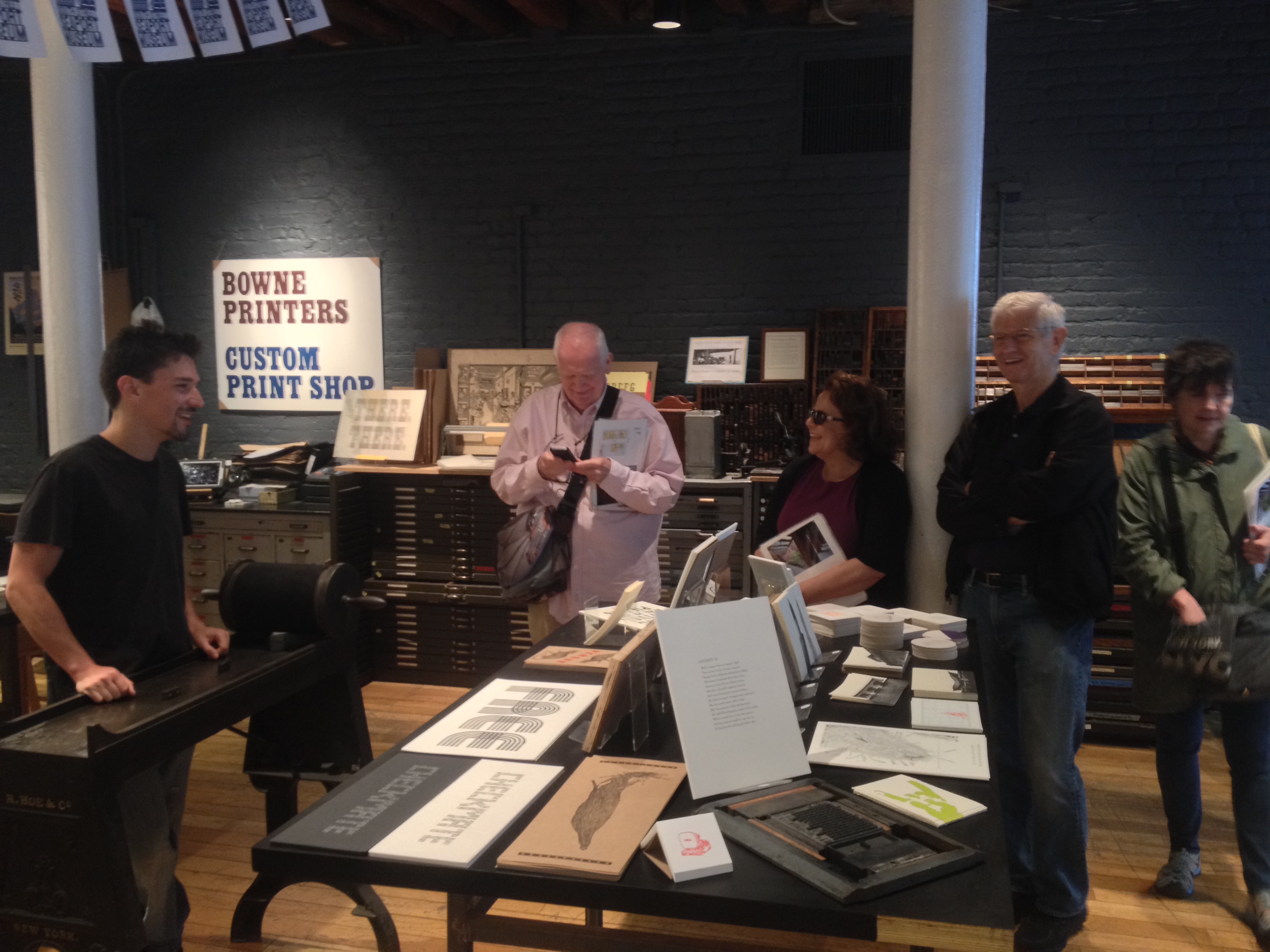

While walking the less traveled side streets near South Street, the absence of stevedores and longshoremen loading cargo, the fishmongers and produce peddlers hawking their goods leaves a feeling of desolation. The South Street Seaport Museum maintains and operates sailing vessels as a vestige of the working waterfront. It also operates Bowne and Co. Stationers and Bowne Printers, housing 19th- and early 20th-century presses that continue to run print jobs. Robert Warner, Ali Osborn, and Gideon Finck maintain what I call New York’s great secrets – a working print shop filled with beautiful letterpress postcards, greeting cards, and writing implements from a pre-digital age. Finck explained the various type in the collection, their use today, and the notion that ports around the globe had hundreds of print shops to handle the printing needs of merchants, shippers, manufacturers, and investors. He detailed the terrible scourge of Hurricane Sandy and the effects East River water had on the wood and metal type. Volunteers came from all over to help rescue this irreplaceable collection.

Lastly, we visited the studio of Naima Rauam in Schermerhorn Row. Rauam has been painting the Fulton Fish Market for over 30 years, and the relocation of the fish market to the Bronx has not stopped her from being inspired by the neighborhood. She described how she once shared space with the last smoked fish house in the district, a building we “read” earlier in the tour with the painted words “FRESH, SALT AND SMOKED FISH” barely legible on the building’s façade. Some of her most recent commissions have been architectural renderings in watercolor. The people in the Seaport District are keeping stories and traditions alive.

The Center for Architecture Foundation has two more upcoming Reading the Streetscape tours in historic neighborhoods:

10.18.14: Reading the Streetscape: The Meatpacking District

and

11.08.14: Reading the Streetscape: SoHo’s Cast Iron Architecture