by Bill Millard

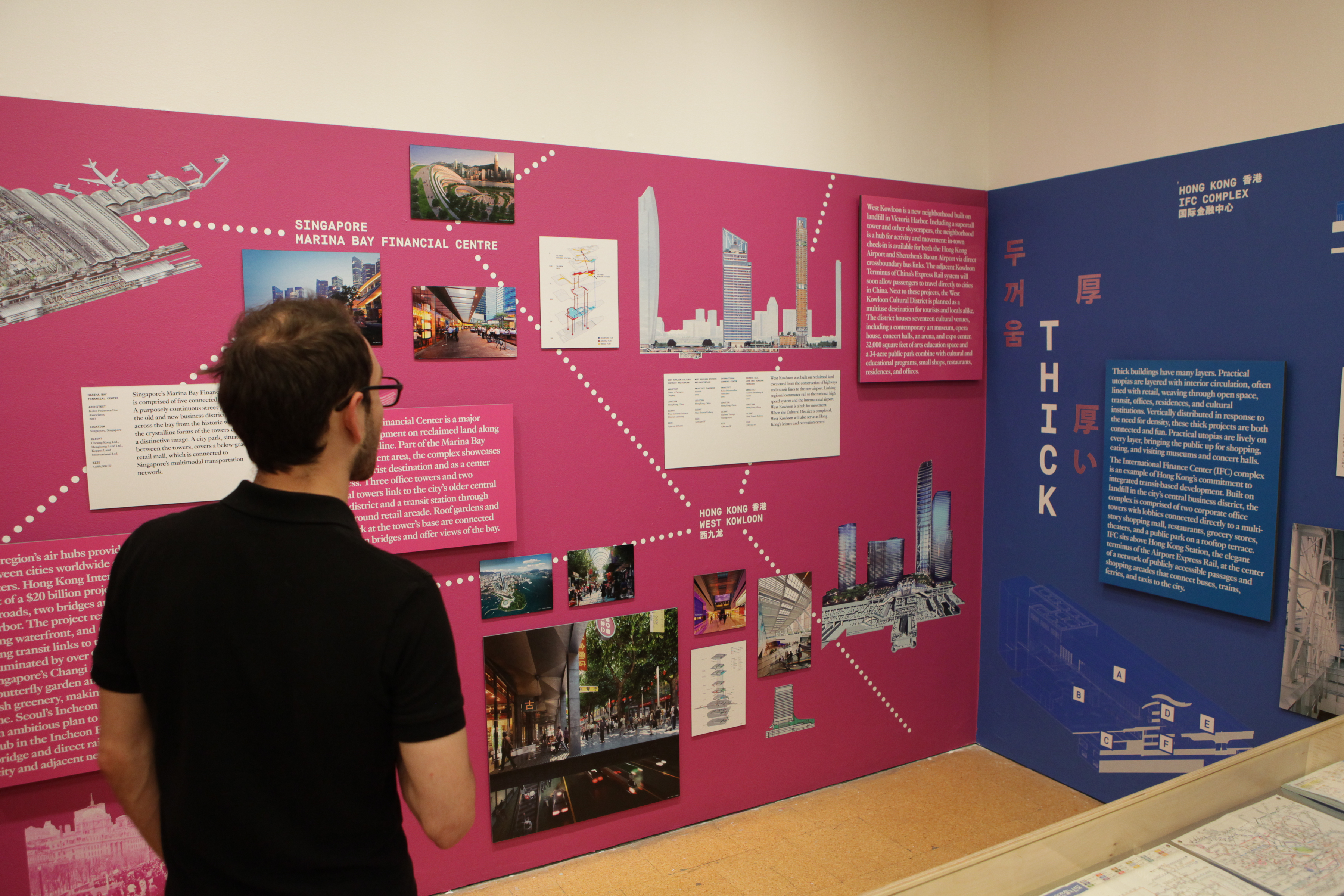

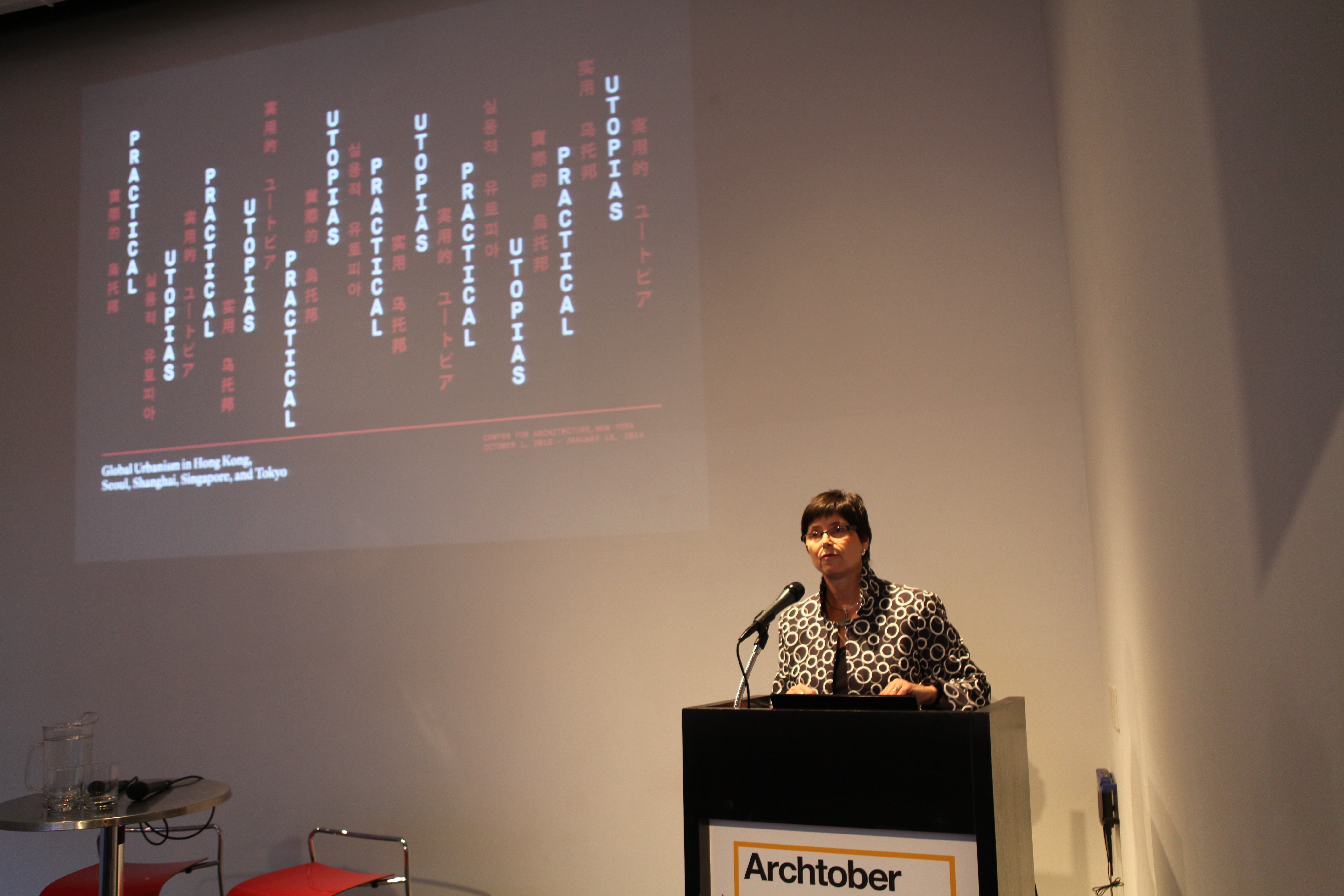

“Practical Utopias,” the Center for Architecture’s new exhibition on global architecture firms’ work in five Asian cities, organizes a wealth of visual and textual information around one neatly oxymoronic title phrase and five simple, potent adjectives. Along with generating a productive tension between practicality and utopianism, these built environments in Hong Kong, Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, and Tokyo are connected, dense, green, thick, and fun. That the exhibition and the accompanying high-profile panel also embodied these five concepts might go without saying, but it deserves to be said. These conversations attracted a crowd dense enough to pack Tafel Hall, developed thick layers of discourse connecting specific questions of design with multidisciplinary considerations, and touched on pressing environmental concerns. And inevitably, any evening bracketed by Daniel Libeskind, AIA’s humane, poetic, historically-grounded design sensibility and Thom Mayne, FAIA’s formidable, rapid-fire syntheses of cutting-edge theory with common sense provided more than the usual share of fun.

As curator Jonathan D. Solomon, AIA, explained in introductory remarks, the five organizing concepts are both straightforward and complex, directly embracing the inherent contradictions and problematic history of utopianism. Utopias have a habit of turning dystopian, he acknowledged. One contributing factor in that process may be that the top-down modernist impulse to foster public life through design was unworkable; in any event, Solomon contended, it is not the appropriate model for these cities, where superimposed functions within tight, dense sites create unprecedented, perhaps unmanageable complexity. “Practical utopias,” he noted, “are compelling precisely because we do not know the future of the city, and how the visions pursued by global architecture in Asia will fit into it.”

Major projects like the Bund reconstruction in Shanghai and Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon Stream recovery evince a widely shared impulse to rededicate space to free pedestrian movement after vehicular incursions, but infrastructural upgrades alone do not create a civic sphere. In these public efforts and in private developments like Tokyo’s mixed-use Roppongi Hills and Hong Kong’s International Financial Center, Solomon continued, “space is made public by its user, not by its designer. Practical utopias will test the flexibility of global space when occupied by local users.” Libeskind offered a complementary emphasis on the genius loci or combined physical and cultural site-specificity that distinguishes, for example, Singapore’s Keppel Bay development, an industrial-turned-residential complex of non-extruded, distinctly curvaceous towers, from mundane, “take-the-money-and-run” megadevelopments.

One recurrent narrative, as formerly colonial cities borrow and transform ideas from earlier-industrializing cities in the West, posits that Asia’s experiments are beginning to instruct the West in turn, closing a historical feedback loop. New York and other Western cities can learn a great deal from the Asian cities that now exceed them in scale; panelists welcomed this tendency while also striking cautionary notes. The unprecedented expansion of some Asian cities raises threats that density will overwhelm carrying capacity; that green design will decline into greenwash as air and water quality are degraded; that connectivity will breed congestion; that thick layering of new architectural forms and programs will obliterate the nuances of treasured vernacular spaces; and that the relentless pursuit of fun in its current varieties will hollow out cultural uniqueness. It is courageous for architects and developers to engage these cities’ very different political leaderships and economic conditions unhesitatingly, aware that these experiments in 21st-century urbanism are moving too fast to yield predictable results.

In such settings, raising certain questions may be preferable to pretending they’re readily answerable. If a globalized world, as Libeskind told interlocutor Cliff Pearson, deputy editor, Architectural Record, “means we want to be at home everywhere,” does that new form of urbanism also make room for one of his own useful creative strategies, deliberately assuming the role of the stranger? When Chinese urbanization is proceeding at a rate unprecedented in human history, can this upheaval make room for the patience recalled by Calvin Tsao, FAIA, principal, Tsao&McKown Architects, who initially experienced working conditions in China in 1982 under I.M. Pei, FAIA, then observed the rapid changes during several return visits, but decided to refrain from building there again until seven years ago? Are preservationism and respect for local traditions actually Western bourgeois constructs with limited relevance to the Asian cities’ aspirations? Ironies abound, as when SHoP Architect’s Christopher Sharples, AIA, discovered he was banned from using Chinese materials associated with “poor things?” (Some clients favor gleaming new icons because they want to be perceived as “having arrived” economically, Sharples finds, even though through Western eyes, the indigenous cultures deserve outsiders’ deference, since “you guys ‘arrived’ hundreds of years ago!”)

A complementary theme, articulated urgently by moderator Vishakha Desai throughout the “Urbanism, Culture, and Quality of Life in Asian Cities” panel, was that 21st-century cities would do well to minimize the facile and often counterproductive (not to mention neo-colonialist) solution of imposing 20th-century Western forms, technologies, and assumptions – even where these are what clients ask for. SO-IL’s Jing Liu has found that academic and social knowledge about techniques of preserving objects and neighborhoods is sometimes missing, and outside specific areas, it may be unrecoverable. With demand in some areas for copies (sometimes literal) of major Western cities, and with the SoHo urbanist model (a wave of creative workers recovering a blighted neighborhood, only to be pushed out by rising rents once deeper-pocketed residents follow) spreading to Asian cities, some brake on the dynamics of market mechanisms is needed. Tsao called for “conscious capitalism” tempered by grassroots experience and an ethical consensus, but questioned whether architects could realistically serve as “shamans to the world.” Sharples added that when a client’s aims clash with an architect’s analysis, “you don’t take the job.”

Mayne’s free-associative style of conversation quickly built up a momentum that went beyond the specific Morphosis project highlighted in the exhibition, the Giant Interactive Group’s headquarters in Shanghai, where the complexity of multiple spatial and functional systems generates an architecture that is biomorphic in a sense having more to do with operations and massive data interpretation than forms. Inside and outside Asia, Mayne’s work has long advanced a flexible, lower-case-F futurism, “formally egalitarian… not married to any single form” and impossible to reduce to a signature. Describing two trajectories in contemporary architecture, a tradition of icons allegedly representing the collective or corporate will and a broader tendency blurring the distinction between architecture and urban planning, he indicated a growing affinity for the latter. Mayne marshaled extensive arrays of historical precedents (from medieval villages to James Stirling to Sigurd Lewerenz to his own generation of architectural intellectuals) in support of bracing improvisations on the perilous, powerless, technician-like position of contemporary architects and the need for a more active embrace of risk, professionally and even politically. Perhaps his best quip involved a journalistic effort to enlist him in speculations about the future: “Future! What an interesting subject. I thought that died in the Fifties.” Mayne’s tongue was pretty clearly in his cheek here, of course: though the brushed-stainless-steel sci-fi Future may be obsolete, one look around this exuberant exhibition reveals that a wholly different future is under construction across the Pacific, at headlong speed.

Bill Millard is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in Oculus, Icon, The Architect’s Newspaper, and other publications.

Event: Practical Utopias at All Scales: The Diversity of International Work in Asia

Location: Center for Architecture, 10.02.13

Speakers: Rick Bell, FAIA, AIANY Executive Director; Jill N. Lerner, FAIA, AIANY 2013 President, and Principal, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates; Jonathan D. Solomon, AIA, Associate Dean, School of Architecture, Syracuse University, and Exhibition Curator; Daniel Libeskind, AIA, Founder, Studio Daniel Libeskind; Cliff Pearson, Deputy Editor, Architectural Record; Vishakha Desai, Special Advisor for Global Affairs, Professor of Professional Practice in the Faculty of International, and Public Affairs, Columbia University, and President Emeritus, Asia Society (moderator); Jing Liu, Principal, SO-IL; Tom Looser, Associate Professor of East Asian Studies, New York University; Chris Sharples, AIA, Principal, SHoP Architects; Calvin Tsao, FAIA, Principal, Tsao&McKown Architects; Thom Mayne, FAIA, Principal, Morphosis Architects; Kent Kleinman, AIA, Dean, Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning; James von Klemperer, FAIA, Design Principal, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (closing remarks)

Organizers: Center for Architecture

Sponsors: Arup, KPF, Lutron (Patrons); Affiliated Engineers, Duggal Visual Solutions, Ennead Architects, Gensler, Hopkins Foodservice Specialists, Jaros Baum & Bolles, Levien & Company, Mancini Duffy | TSC, New York University, Perkins Eastman, Porcelanosa Group, Robert A.M. Stern Architects, Robert Silman Associates, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Vanguard Construction & Development Co. (Sponsors); Anonymous, Art of Vinyl, FXFOWLE Architects, Hong Kong Economic & Trade Office New York, JFK&M Consulting Group, New York Building Congress, Syska Hennessy Group, TEN Arquitectos, Vantage Technology Consulting, and Weidlinger Associates (Supporters)