by Camila Schaulson Frenz

As the title suggests, “BEIRUT NOW | A Panel On Urban Landscape’s Conflicting Desires” was an evening of binary oppositions. Steeped in nostalgia, it contrasted the inclusive Beirut of the past with the exclusive Beirut of the present, and pitted neo-liberal interests against the desires of those who long for a Beirut attached to its local culture and historical heritage. In fact, nostalgia is, as Nishan Kazazian, AIA, founder of Nishan Kazazian Architecture, stated, a conflicting concept itself, invoking a “paradoxical combination of hope and hopelessness, space and place.”

Setting the tone for the evening, Kazazian took the audience through a haptic journey of the Beirut of his childhood, tracking the route that he took from his home to the center of the city. The urban morphology of 1950s Beirut, he posited, created opportunities for people of different socioeconomic backgrounds to interact and intermix. This “undivided city” not only impacted the formation of his ideas, but also offered a “model of coexistence that may have been emulated at a global level.”

These nostalgic references to the Beirut of the past are contrasted by the Beirut of the present – what Kazazian describes as a “manmade disfigurement.” To him, the Beirut Central District (BCD) is a “void,” a site of empty spaces and “scattered developments of conflicting, dissonant styles intended for the 1%.”

So what separates these two radically different conceptions of the city? To Simone Kosremelli, an architect and urban planner based in Beirut, “For every Beiruti now, there is Beirut before 1975 and the Beirut after 1975.” The year marks the beginning of 15 years of civil war, during which the souks were looted and the BCD became a no-man’s land, taken over by squatters with no access to water or electricity.

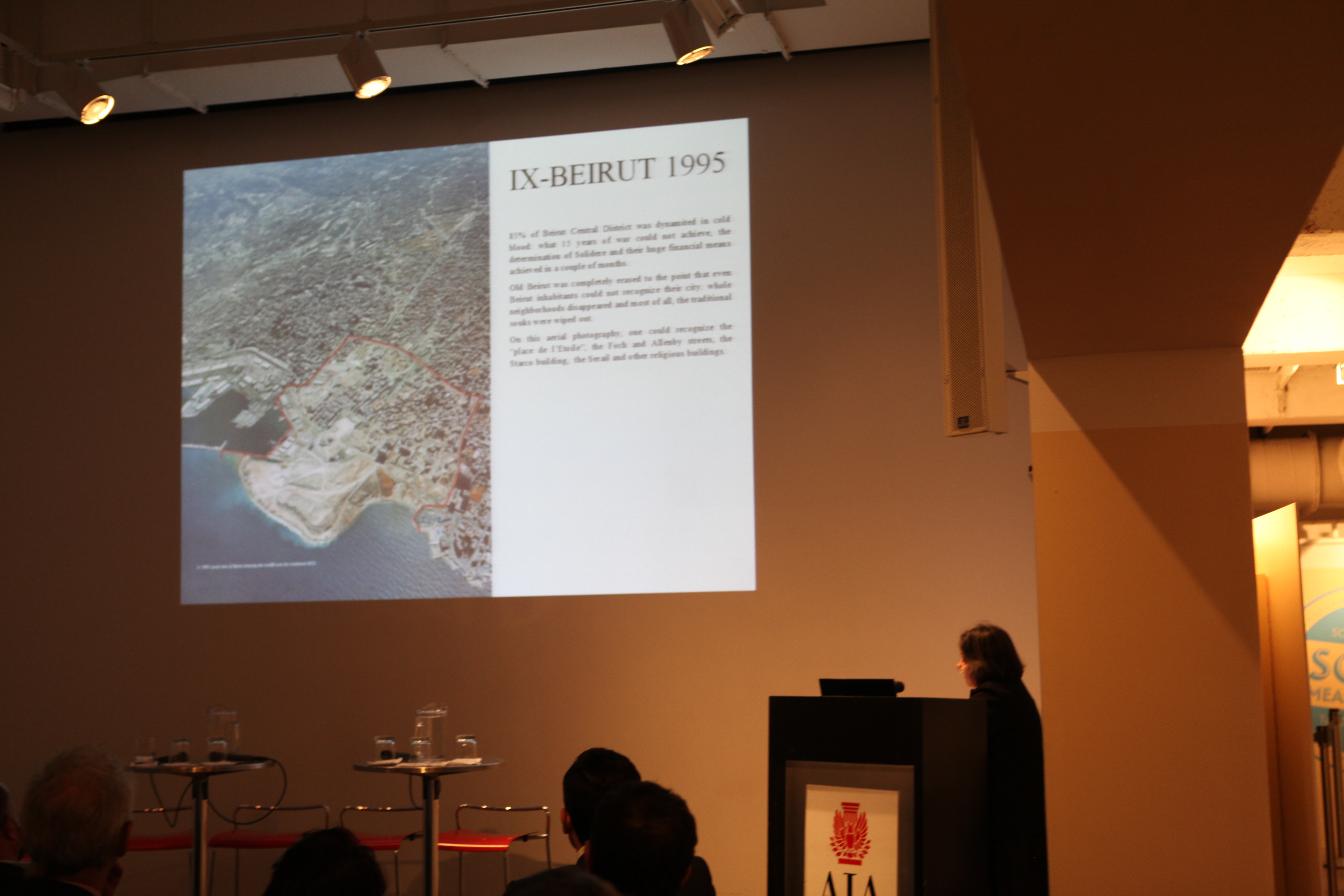

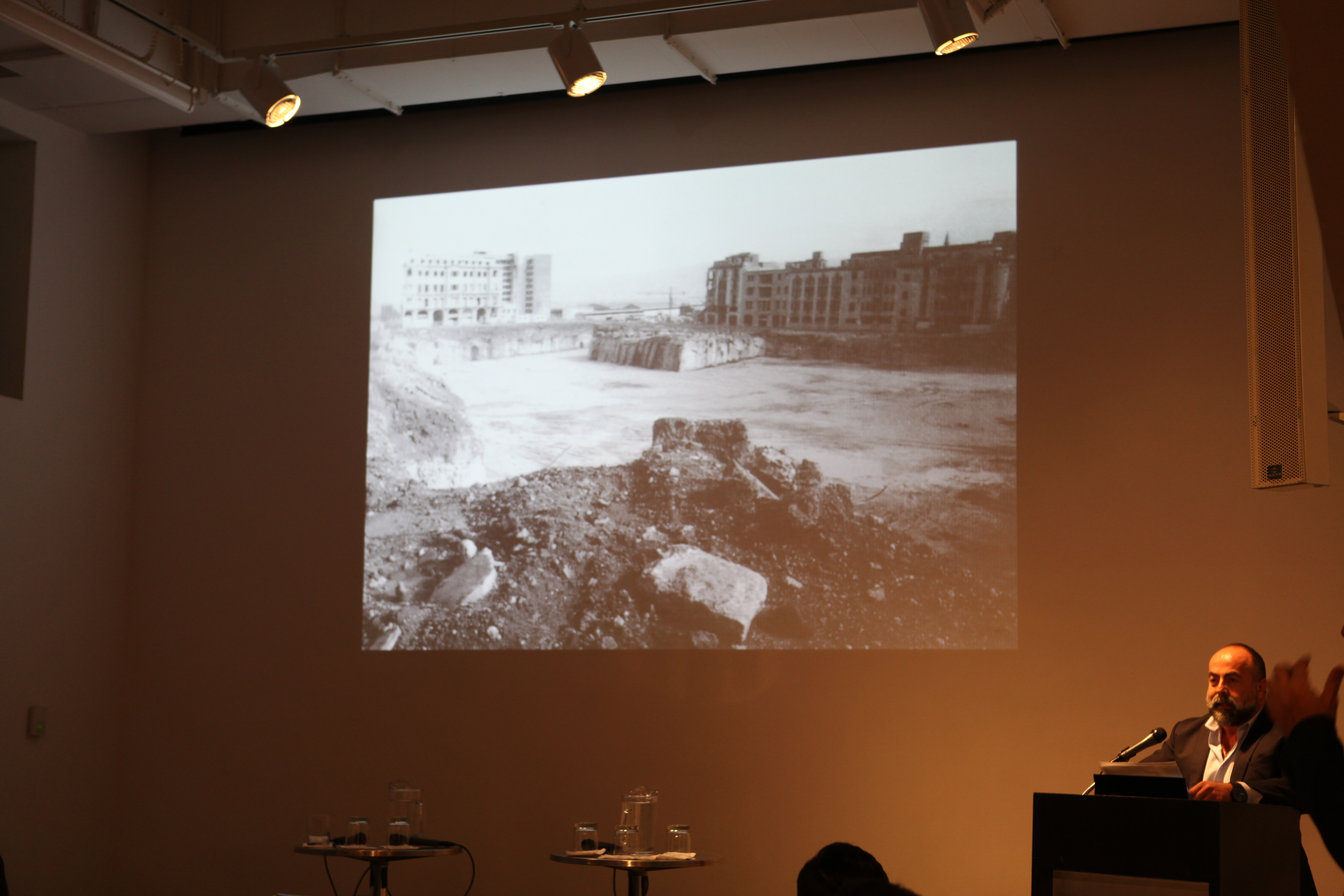

Between the Beiruts of yesterday and today, the spiritually and culturally devoid space described by Kazazian, there is also a tremendous physical void. In 1994, Lebanon’s Prime Minister Rafik Hariri founded Solidere, a joint-stock company that was given full control over the planning and redeveloping of the BCD. Before the reconstruction could begin, however, Solidere demolished 85% of the central district’s building stock, including its many souks.

Rodolphe El-Khoury, director of Urban Design at the University of Toronto and partner at Khoury Levit Fong, presented a text he wrote in the 1990s analyzing the monumental demolition process and attempting to find an explanation for why the “dusty field” was drawing in so many crowds. El-Khoury described this as “a morbid fixation on the scene of the absent center.” His hopes for the city’s reconstruction, however, were bleak, noting that even “the negative but still gratifying encounter with the sublime may be lost altogether once the site is reclaimed…no matter what we build on this site…losses will linger and indifference will grow.”

Unfortunately, El-Khoury’s prognostications were prophetic. The Solidere souks that replaced the original structures kept the same names and were located on the same streets as their predecessors. Solidere co-opted Beirut’s architects, originally opposed to the site’s demolition, to build new structures, more akin to mega-malls than the former open air merchant markets. “Thinking that keeping the name will keep the spirit is not enough – the spirit is the people,” lamented Kosremelli.

Despite the tragedy of the BCD, speakers presented the audience with a glimmer of hope in the form of the northeastern suburb of Bourj Hammoud, a portion of the city settled by Armenian families who escaped from the 1920s genocide. Arpi Mangassarian, a Beirut-based architect and urbanist, spoke about the challenges facing the neighborhood, including the tear of the urban fabric resulting from the construction of elevated highways that divide the city, and the displacement of long-time residents. However, it is in this suburb where Beirut’s souks of days past have flourished. Its narrow, human-scaled streets and lively markets embody the city’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

The unfortunate circumstances of Beirut’s reconstruction described by the speakers served as a sample case from which the panel, moderated by Brian McGrath, dean of Parsons The New School for Design School of Constructed Environments, built upon broader ideas. Although the large-scale demolition of Beirut is a particularly good example, according to Miguel Robles-Durán, director of MS Design and Urban Ecologies Graduate Program at Parsons; Aseel Sawalha, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Fordham University; and Michael Stanton, Past Chair of the Department of Architecture and Design at the American University of Beirut, the replacement of the BCD’s traditional souks with high-end international brands is a trend that is also reproduced in New York City and throughout the rest of the world.

It is an issue, Robles-Durán said, that relates to Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the “right to the city.” The transformations of our urban environments are a physical manifestation of the imbalance of that right, with neoliberal forces shaping our cities based on the imaginary of the few. Sawalha sees these structures as being built for outsiders, catering to the unknown, affluent tourist rather than the local population. All over the world, architecture indebted to local traditions is being replaced by what Kazazian described as “white elephants, capable of surviving anywhere from the north to the south poles.”

The panelists all agreed that the forces at play are deeply concerned with the power of memory and its essential role in engaging us with our past. Author Nancy Kricorian views each of her historical novels as small works of preservation – narratives of memories encoded in place and time. It is by denying the power of memory that architects become complicit, allowing decontextualized, abstracted buildings to insert themselves into our urban fabric. Kosremelli blamed the indifference of Beirut’s young generation on the 15 years of civil war that made the BCD inaccessible, severing their ties with the city’s traditional core. Without a connection to what was there before, new urban morphologies that increase the social divides of the city can more easily be seen as natural. And although Robles-Durán advocated a complete retooling of the architecture profession, lest architects “continue to decorate power,” Kazazian keeps his faith in architecture regaining the public realm, one building at a time.

Event: BEIRUT NOW | A Panel On Urban Landscape’s Conflicting Desires

Location: Center for Architecture, 11.12.13

Speakers: Rodolphe El-Khoury, Director of Urban Design, University of Toronto, and Partner, Khoury Levit Fong; Nishan Kazazian, AIA, Founder, Nishan Kazazian Architecture; Simone Kosremelli, Architect and Urban Planner; Nancy Kricorian, Author, Zabelle, Dreams of Bread and Fire and All the Light There Was; Arpi Mangassarian, Architect and Urbanist (speakers); Brian McGrath, Dean, School of Constructed Environments, Parsons, The New School for Design, and Founder and Principal, Urban-Interface (moderator); Miguel Robles-Durán, Director, MS Design and Urban Ecologies Graduate Program, Parsons, The New School for Design; Aseel Sawalha, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Fordham University, and Author, Reconstructing Beirut: Memory and Space in a Postwar Arab City; and Michael Stanton, Past Chair, Department of Architecture and Design, American University of Beirut, and Professor, School of Architecture Planning and Preservation, University of Maryland (discussants); Rick Bell, FAIA, AIANY Executive Director (opening remarks)

Organized by: Center for Architecture